Chapter 7: Medical English

In this chapter you will learn….

To ensure safe communication in distress and emergency situations the student can, in hypothetical distress situations, communicate in English.

Medical English:

- Have sufficient English vocabulary for body parts and items used in basic First Aid treatment.

- Explain injuries and request medical assistance in English

Elementary first aid and the importance of English

This section will focus on medical English and is based on Model Course 1.13 Elementary First Aid and Model Course 1.14 Medical First Aid. These two model courses found the basis for the elementary and advanced medical courses, which is a part of the compulsory education. The latter, Medical First Aid, is mainly extracts from International Medical Guide for Ships[1]. This is a free of charge publication from The World Health Organization, which among other things, provides general descriptions of symptoms or diseases, key questions to ask the injured, and do’s and don’ts when assisting an injured individual. Other publications you should have on hand are The Ship Captain's Medical Guide2 , which is a guide from the UK Government that provides an overview and advice on first aid and treatment of injuries and illnesses, as well as the two the two Model Courses and the book Medicine on Board (Schreiner and Aanderud, 2008). Also, The Norwegian Centre for Maritime Medicine’s webpage3 is a good resource on the subject, including the textbook of Maritime medicine .4

The following tasks and exercises are made based on information given in these publications, and the aim is to:

- Enhance vocabulary

- Explain injuries

- Request medical assistance

note

It must be emphasized that this section aims to increase the level of medical English vocabulary, it is not a course in First aid.

Importance of Medical English

Situations where you must exercise elementary first aid, or even so medical first aid, are likely to occur when you work at sea. The fact that you might be far away from shore and medical assistance, makes it even more crucial for each crewmember to know the basic principles of first aid. The Safety Course and other aspects of your education as officers instruct you how to correctly respond in emergency situations. Your training, practice, and solid theoretical knowledge should provide you with the ability to carry out first aid and handle stressful events regardless of language. However, in addition to proper training and education, advanced medical English is necessary when communicating with Radio Medico, taking commands, and talking to colleagues in the event of a medical emergency. This section aims therefore to provide the medical English vocabulary needed for effective communication in a medical emergency.

All crewmembers should be prepared to do first aid as certain conditions require immediate treatment for the patient to survive. However, it is important to recognize one’s limitations, as treatment of most injuries and medical emergencies can be postponed until a skilled first-aider is on scene. “Procedures and techniques beyond the rescuer’s ability should not be attempted. More harm than good might result” (WHO, 2007).

What is first aid?

– Emergency treatment given before professional medical services can be obtain

– Treatment given to prevent death, further injury, counteract shock and relieve pain.

General principles of first aid aboard ship

First aid must be administered immediately to:

- restore breathing and heart-beat;

- control bleeding;

- remove poisons;

- prevent further injury to the patient (for instance, removing a person from a room containing carbon dioxide

The following is a basic life support sequence checklist. This is a life support sequence with questions and what to do depending on the answer, like the one you can find in the International Medical Guide for Ships (WHO, 2007).

A basic life support sequence

Does the patient

| Respond to shaking and shouting? | NO |

| Breathe? | YES |

| Have a heart beat? | YES |

What to do

1. Put patient in recovery position

2. Check for other life-threatening conditions

Does the patient

| Respond to shake and shout? | NO |

| Breathe? | NO |

| Heart beats? | YES |

What to do?

1. Clear airway

2. Apply rescue breathing

Does the patient

| Respond to shake and shout? | NO |

| Breathe? | NO |

| Heart beats? | NO |

What to do?

1. Apply cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

- Figure 1 A basic life support sequence, 2007*

The recovery position

Figure 1 A basic life support sequence, 2007

The following sequence is from website of St. Johns Ambulance (n.d.) and explains in three steps how to put a patient in the recovery position:

Kneel down next to the patent on the floor.

Follow the next three steps if you find someone lying on their back. If you find them lying on their side or their front you may not need all three:

- Place the patient’s arm nearest you at a right angle to the body, with the palm facing upwards.

- Take the other arm and place it across the chest so the back of the hand is against the cheek nearest you, and hold it there

- With your other hand, lift the far knee and pull it up until the foot is flat on the floor. Now you’re ready to roll the patient onto his/hers side. Carefully pull on the bent knee and roll the patient towards you. Once you’ve done this, the top arm should be supporting the head and the bent leg should be on the floor to stop them from rolling over too far.

Important

Next, it is very important that you check that their airway is open, so the patient can breathe and any blood or vomit in the mouth can drain away. To do this, tilt the head back, gently tilt the chin forward and make sure that the airway will stay open and clear.

If you suspect a spinal injury

If you suspect that they might have a spinal injury and need to place them in the recovery position because you cannot keep their airway open, do your best to keep their spine as straight as you possibly can:

– To open their airway, instead of tilting their neck, use the jaw thrust technique: Place your hands on either side of their face. With your fingertips gently lift the jaw to open the airway, avoid moving their neck

– To roll them onto their side, use the normal technique but do your best to keep their spine as straight as you can. If possible, get up to four helpers, two on each side, to help you keep their head, upper body and legs in a straight line at all times as you roll the body over

(St. John Ambulance , n.d.).

Loss of responsiveness and CPR

If a patient has lost responsiveness, immediate action is crucial. What kind of action needed varies; why is the person unresponsive, is he/she breathing or not and is it an adult or a child. If the person is non-responsive and not breathing, you need to start CPR. Visit the webpage of St.Johns Ambulance for further information, info-posters and videos.

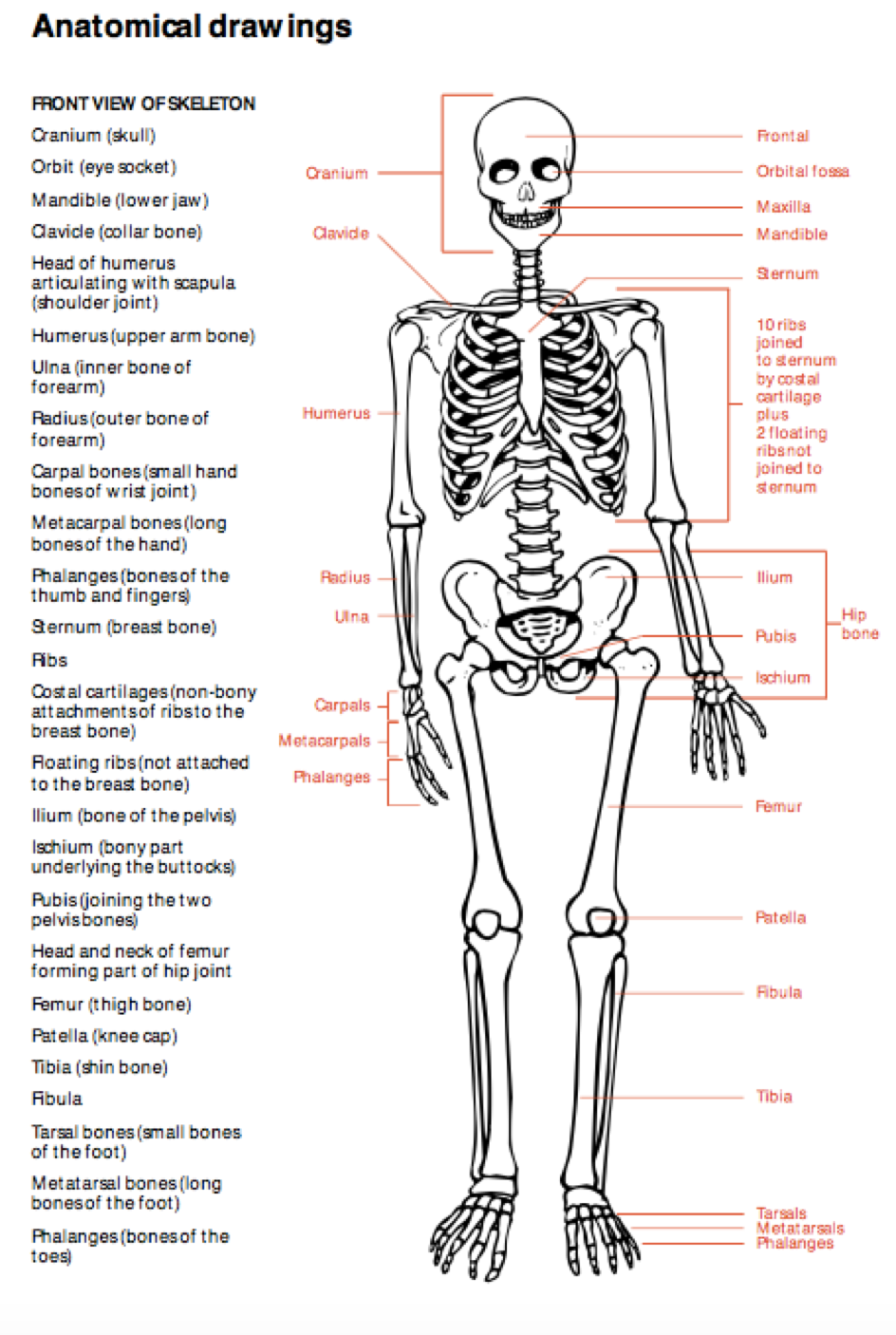

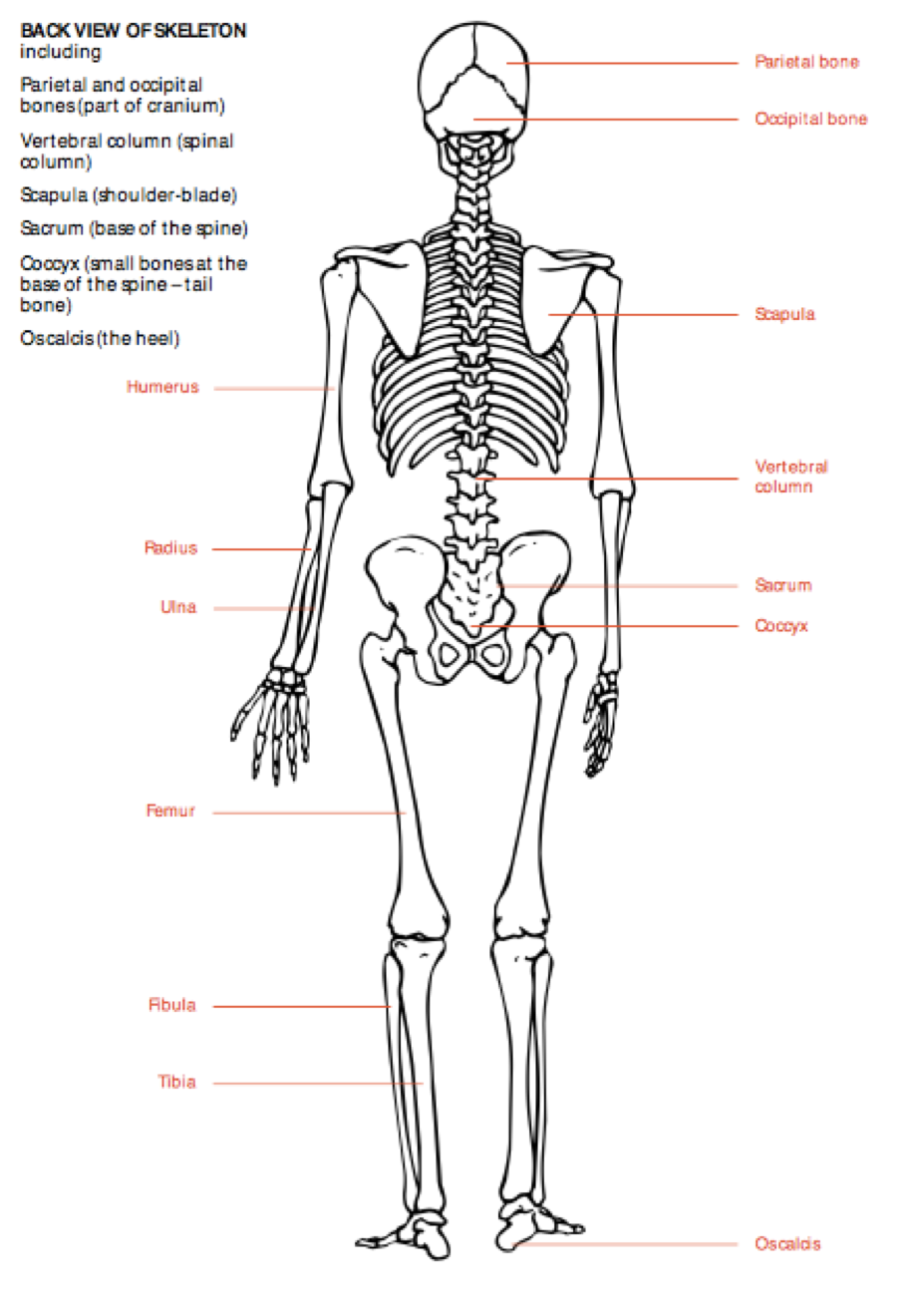

Basic anatomy and physiology

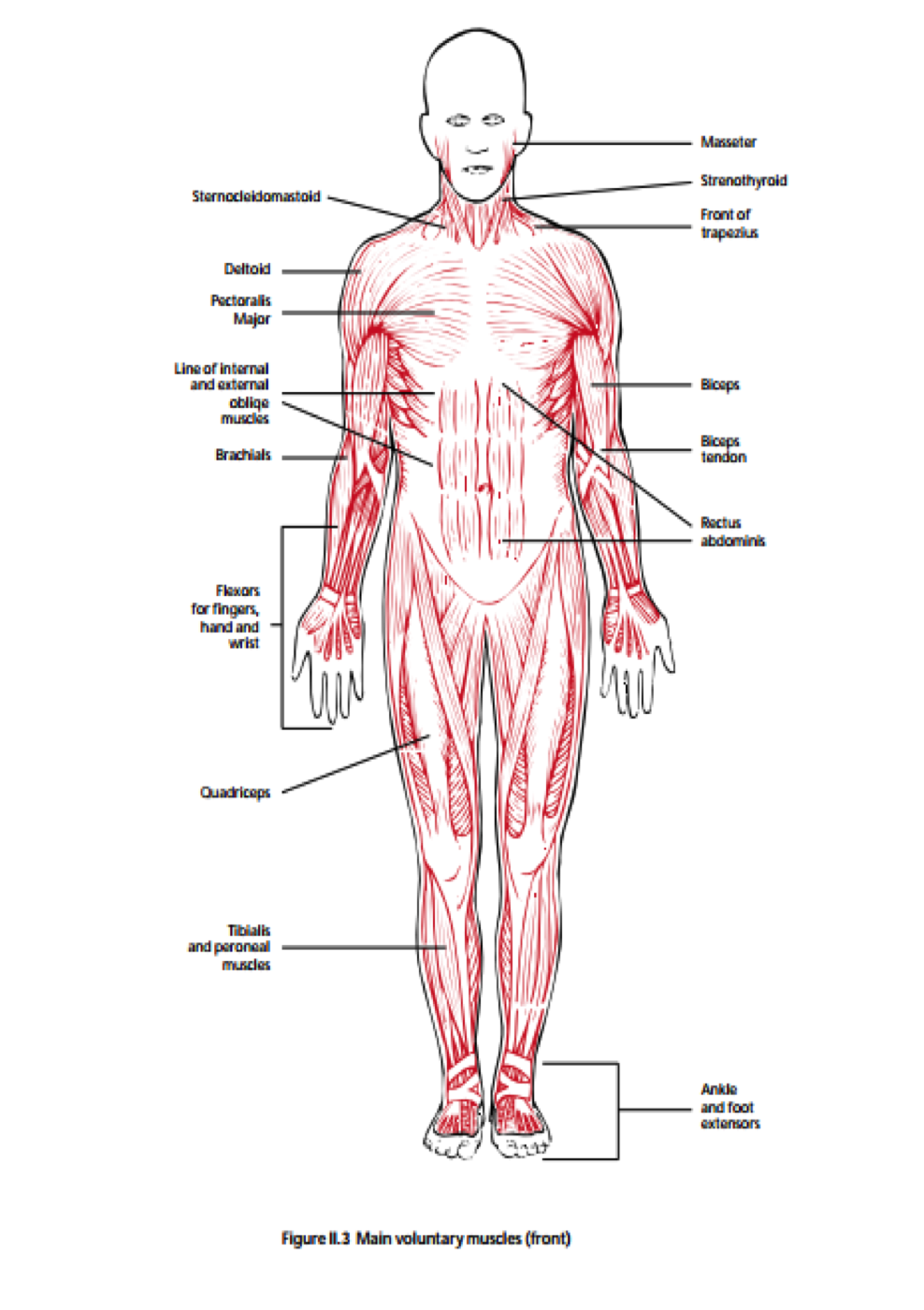

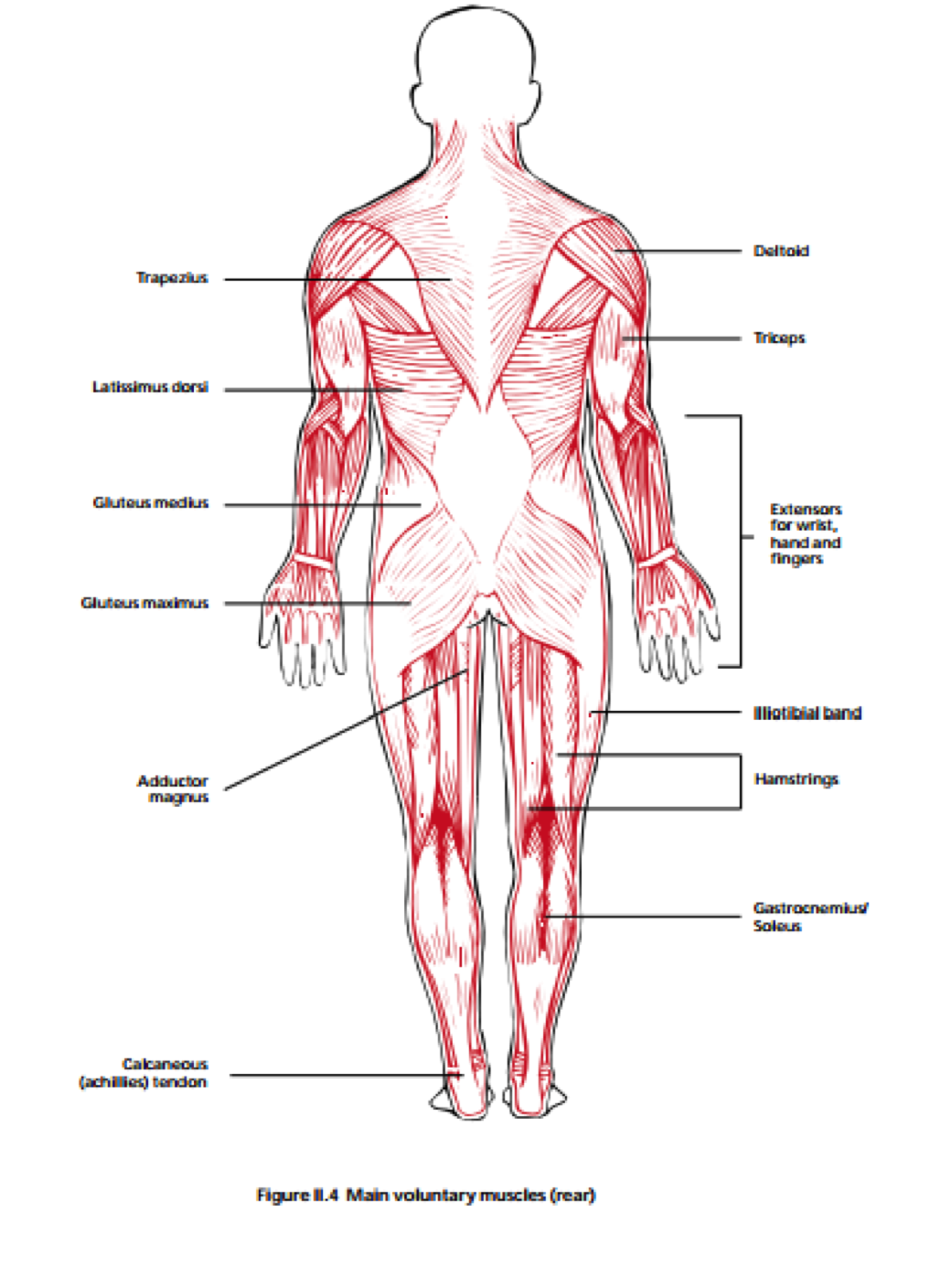

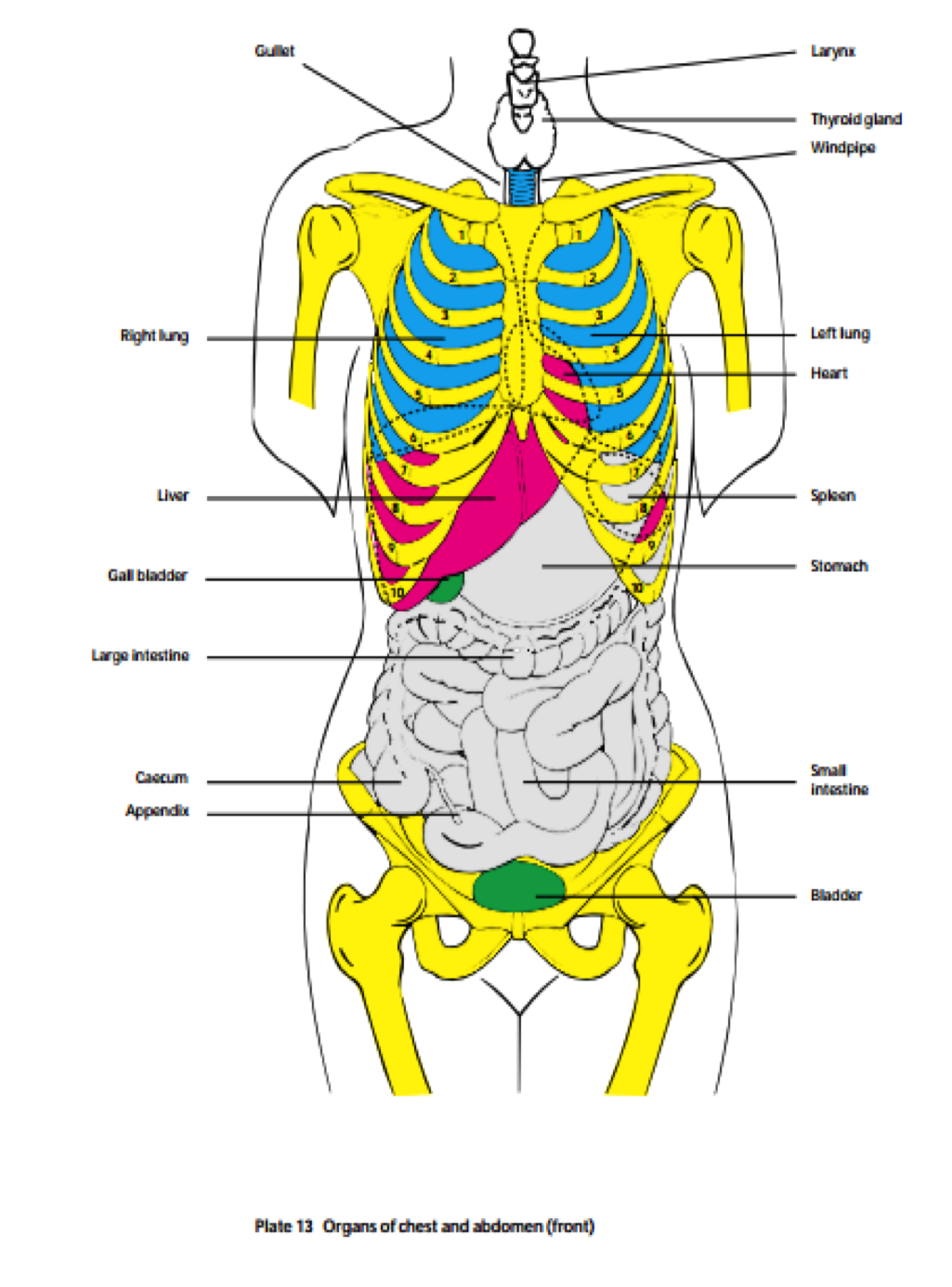

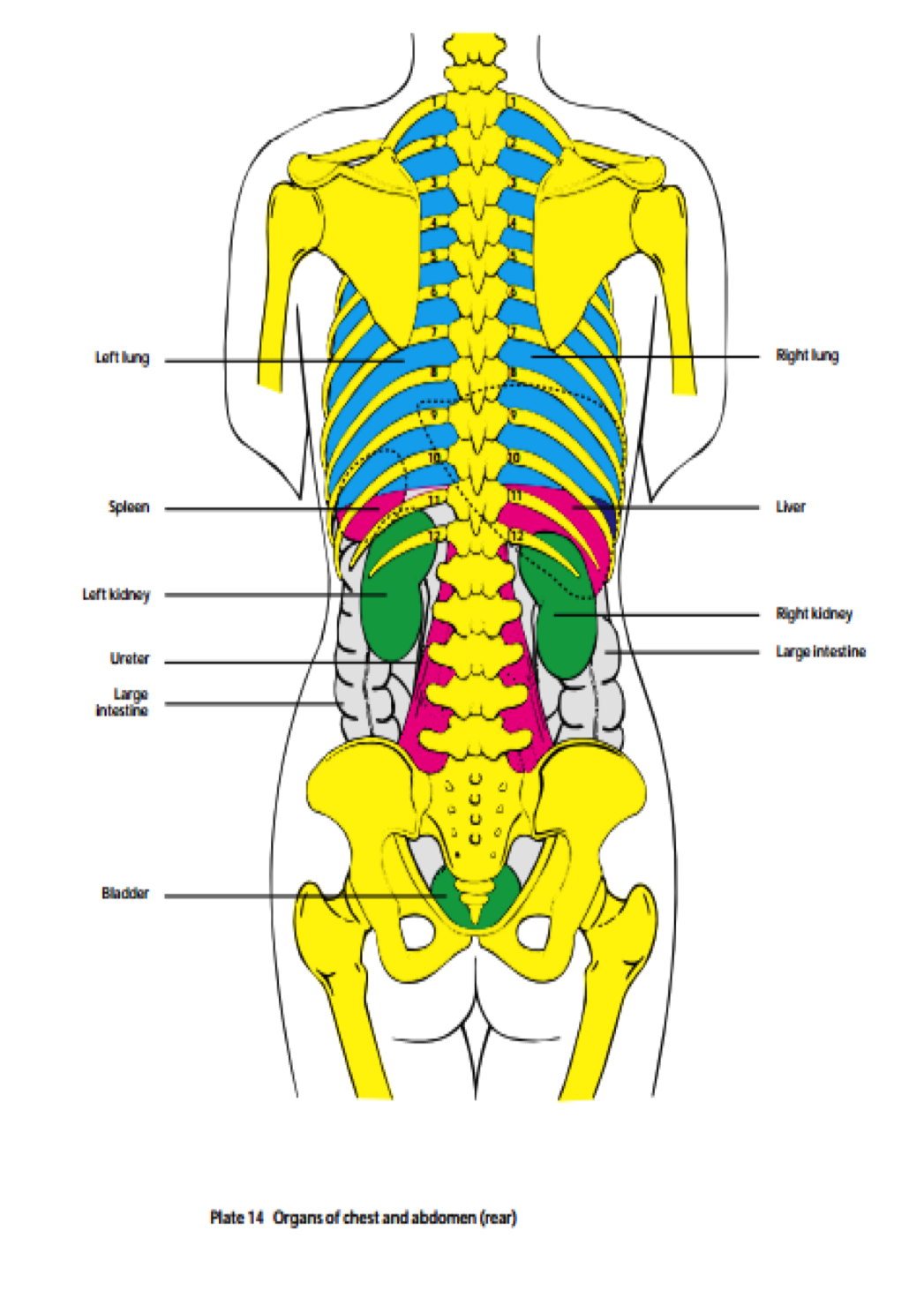

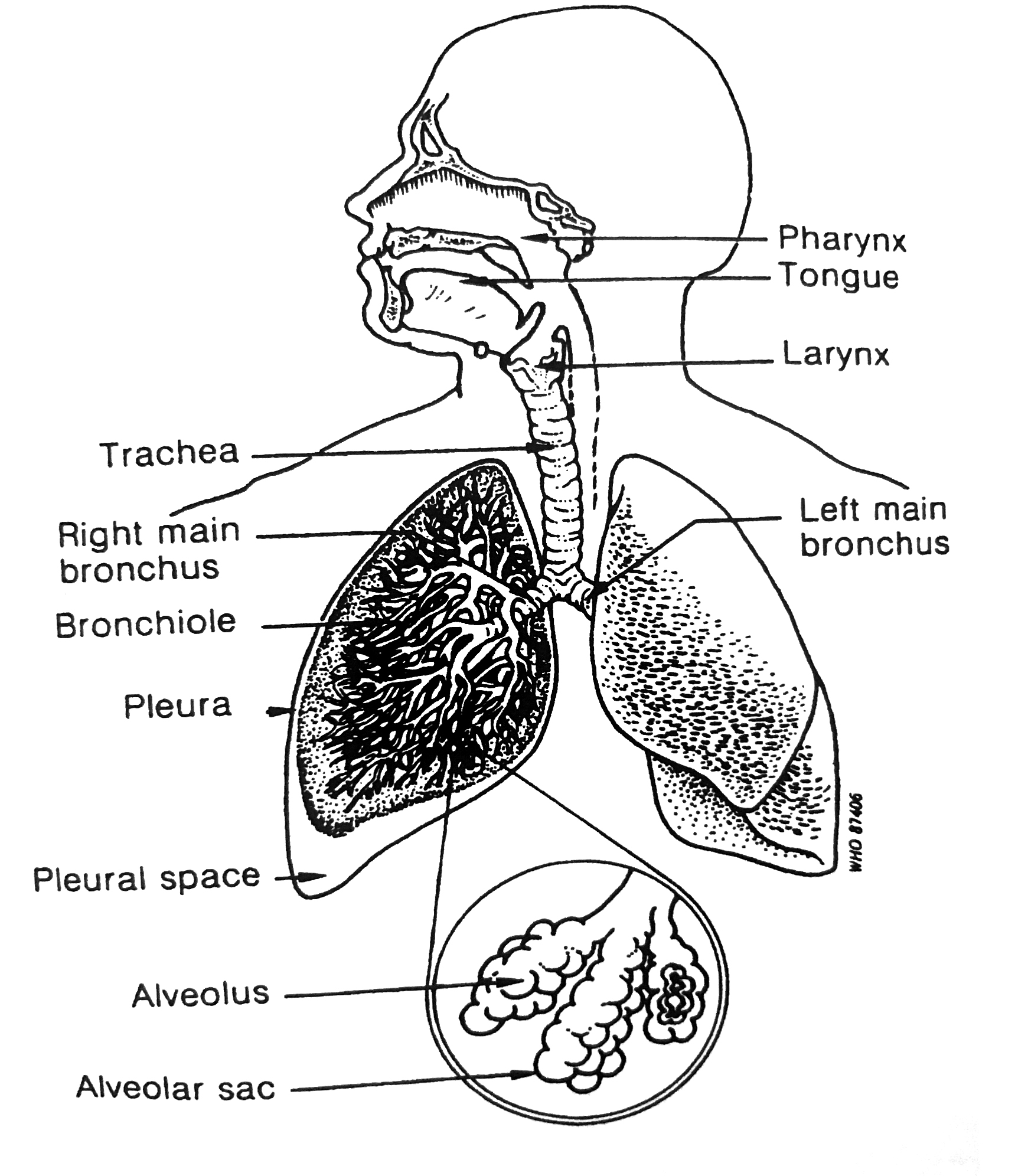

Not only when doing first aid, but also when seeking advice from Radio Medico or discussing injuries and treatments with other crewmembers, it is very important to know the proper names of the different body parts, muscles, bones and organs. Contrary to Norwegian, English has kept a lot of the Latin terminology for the skeletal, muscular and respiratory system. In the following, you will find anatomical drawings of the skeletal system, the muscular system, the respiratory system and organs of the chest and abdomen.

The skeletal system

Figurere 2 (Maritime and Coastguard Agency, 2014)

Figure 3 ibid.

The muscular system

Figure 4 ibid.

Figure 5 ibid.

Organs of chest and abdomen

Figure 6 ibid.

Figure 7

The respiratory system

Figure 8 (WHO, 2007)

Injuries: Typical injuries and first aid treatment

Under, you’ll see lists of acute life-threatening situations and injuries you as a first aider at sea should know of and recognize. Further information about the injuries or acute situations, what to do and how to treat them is to be found in the different publications.

Acute life-threatening situations (Schreiner, A. & Aanderud L., 2007) are:

Unconsciousness: International Medical Guide for Ships pp.121, Medicine on board pp. 22, Ship Captain’s Medical Guide pp. 63

Shock: International Medical Guide for Ships pp.13, Medicine on board pp.23, Ship Captain’s Medical Guide p. 19

Bleeding: International Medical Guide for Ships pp.10, Medicine on board pp.24, Ship Captain’s Medical Guide pp. 14 and pp. 20

Convulsion: Ship Captain’s Medical Guide pp. 19, Medicine on board pp. 26

Drowning and man overboard: International Medical Guide for Ships pp. 341, , Medicine on board pp.27, Ship Captain’s Medical Guide pp. 201

Life threatening infections; International Medical Guide for Ships pp. 254, Medicine on board pp.28

Injuries (ibid)

- Head injuries

- Spinal column and neck injuries

- Facial Injuries

- Severe bleeding

- Shock

- Clothing on fire

- Burns and scalds

- Fractures

- Blast injuries

- Internal bleeding

- Choking, suffocation and strangulation (International medical guide for ships)

Exercises

- Kahoot or ITSL-quiz to test vocabulary. The students can make their own Kahoots.

- Pronunciation

- Explain a couple of the most typical injuries or acute situations, including first aid

- Quiz cards with the injuries in question

- Role play: Information about an injury, fill out case record and “contact” Radio Medico

- MAREng’s activities dealing with first aid and Radio Medico

Request medical assistance: Call for medical help

Mariners are often of good health, but the work environment can be dangerous and hence both injuries and illnesses can occur. It is the Medical Officer’s decision whether to treat commonplace conditions or to consult Radio Medico. However, one should always contact Radio Medico in acute and serious situations. According to Schreiner and Sørensen (2008, p.17) situations requiring immediate aid are:

- serious injury

- sudden unconsciousness

- severe breathing difficulty

- acute pain in chest or abdomen

- high fever, over 40° C

- extensive burns covering more than 5% of body surface

- serious mental disorder

- poisoning with acute symptoms

In life-threatening situations, you should always telephone, other types of communications are too slow.

Radio Medico Norway– Be prepared when calling the doctor

In order for the doctors at Radio Medico Norway (RMN) to be able to do the best possible job, it is important to examine the patient before making a call. Here are some useful tips to on how to do so.

CHALLENGING TASKS

It can be a challenge to serve as a doctor on duty in RMN. The doctor must as best he can make a diagnosis and suggest treatment without being able to see or examine the patient face to face. It is not possible to carry out regular blood tests, x-ray, ultrasound or other medical examinations that are a matter of routine ashore. Moreover, the doctor does not know the person examining the patient on board, nor anything about this person’s education, training and skills.

Language is often a significant challenge. It is even more difficult for the doctor to form a picture of the situation when an interpreter is used. Speaking directly with the patient can sometimes be useful, and being emailed a regular snapshot can often be of great benefit.

RMN has established an advanced receiving system for video consultations with ships. The system also includes video consultation equipment in relevant specialist departments at the hospital. Unfortunately, only a few ships have taken the appropriate measures in order to use video as a diagnostic tool and a treatment aid. Today there are simple and inexpensive solutions to establish video consultations between ships and RMN.

THE FIRST CALL

In cases of serious and life-threatening conditions, immediate life-saving measures will often be required before contacting RMN. If a member of the crew is available and able to establish contact, this should be done simultaneously. In such cases, it is appropriate to establish contact without necessarily having prepared. In cases of less severe conditions, you normally have the time and opportunity to prepare before contacting RMN.

Doctors on duty regularly experience that the caller has not examined the patient at all. In cases of a toothache or a sore throat, we often experience that no one has had a look into the patient’s mouth before calling the doctor. In cases of eyestrain, the patient has often not been asked whether his vision is normal. It frequently happens that the caller claims that the patient has fever, or that he has not, even though his body temperature has not been measured. In cases of abdominal pain, it is likely that no one has examined the patient’s abdomen or tested his urine using a urine test strip.

Unfortunately, it is often the case that the patient is not nearby when RMN is contacted. This leads to unnecessary time being spent carrying out further examinations and having clarifying questions answered. Nevertheless, many people contacting RMN deserve recognition for having prepared well, showing good insight, and having knowledge and skills corresponding to the training objectives of the STCW convention.

GENERAL ADVICE ON PREPARATION

The patient must (if possible) be together with the person contacting RMN.

- How has the condition developed?

- When did it start?

- How did it start?

- Quick, slow or no worsening?

- Stable condition or improving?

- Does anything worsen the symptoms?

In most cases of illness, it is important to measure the body temperature. The temperature should preferably be measured in the anus, but in some cultures, this is unacceptable. Remember to take into account whether the patient has taken an antipyretic before measuring the temperature.

Pulse rate and pulse rhythm are important indicators of the health of a patient, and a measurement thereof is particularly important in the event of severe injury or suspected serious disease. The blood pressure is of importance, but do not spend too much time trying to find the equipment and carrying out measurements if the health condition requires a quick response.

The breathing rate is especially important in the event of severe injury or suspected serious disease. Remember that a breath includes both an inhale and an exhale. It is most convenient to count the number of inhales per minute, which gives the breathing frequency.

In cases of pain, it is important to describe whether the pain is constant or colc-like/cramp-like and whether the condition is worsening, stable or improving. Does anything worsen the pain? Does the patient prefer to lie down or sit still, or is it better to move around? Has the pain moved? Is the pain radiating, and if so, where to? Has the patient taken any painkillers? If so, what kind of painkillers, how much and at what time?

In all cases of urinary tract symptoms, it is important to check the urine with a urine test strip. Is the urine production and urination normal, or has it changed? Has the patient noticed any discharge from the urethra? If so, what does it look like? The body temperature must be measured. Could it be a sexually transmitted disease?

Pain/symptoms in the abdominal/stomach area must be carefully examined. It is difficult to examine the abdomen, and instructions from the doctor on duty will often be required. The abdomen must be pressed gently and systematically to find out where it hurts. Press harder if necessary. Does the patient feel more pain in the abdomen when couching, lifting a leg, trying to do a sit-up or rising up from/laying down on an examination bench or a berth? Findings on any of these are likely to be signs of irritation of the peritoneum, which may indicate a serious condition. Does the patient suffer from diarrhoea or vomiting? Is the patient eating and drinking?

LOGICAL THINKING

This list is not complete. When encountering a patient, you must think logically and try to figure out what you and the doctor need to know to approach a diagnosis. Doing so will make you well prepared for a call to RMN.

If you consider it likely that deviation or evacuation of the patient will need to take place, it is a good idea to figure out in advance which alternatives exist, and what the expected timescale would be. However, you should not waste time doing this if it is urgent to contact RMN.

RMN’s doctor on duty must often make important judgements that may have a major impact on the outcome of the disease for each patient, on the use of essential emergency resources and on the ship’s operations. It is very important that the doctor make judgements based on the best information possible. As the person responsible for medical matters on board, you play a central role in this context.

It is of the utmost importance that you are aware that the presumed diagnosis may be incorrect. The treatment initiated may be incorrect. The condition may worsen. It is therefore necessary that the patient be carefully observed until he is considered recovered. Call RMN again if the development is not satisfactory. The patient and doctor on call both depend on you to take responsibility.

ORGANISING THE EMERGENCY SERVICE

Five doctors share the watch. The doctor is on call day and night for a whole week. He performs the watch duties in addition to his regular work in this period. He thus has the emergency phone nearby for a whole week; at work, while travelling, at the store, in the car, at parties and by the bed. There are normally few inquiries during the night, which makes it possible for the doctor to perform his regular assignments at daytime. You should of course contact RMN at any time of the or night if you find it necessary. When the ship is in port, the right thing to do is to contact the local health services for examination and treatment. Unfortunately, distances do not allow us to establish an arrangement which involves an emergency centre with a doctor present around the clock. (Ulven, 2017)

Exercise:

Write a summary of the text where you emphasise the most important things to remember when calling Radio Medico

Case record

In the following you see Radio Medico’s case record and observation form

|

Patients name: |

Rank and occupation on board:

|

||||

|

Date of birth: |

Sex: |

Nationality: |

Date, UTC:

|

||

|

Vessel name: |

Next port of call: |

ETA, UTC:

|

|||

|

Position:

|

Call sign: |

Port of departure: |

Nearest port: |

||

|

Communication by: |

Satellite no: |

Time of first contact with Radio Medico:

|

|||

|

Previous illnesses/allergies:

|

|||||

|

Medications:

|

|||||

|

Present symptoms/complaints:

|

|||||

|

Examination finding(s):

|

|||||

|

Blood pressure: |

Pulse rate: |

Respiration rate:

|

|||

|

Radio Medico’s orders:

|

|||||

|

Outcome (reported fit on board, sent home, admitted to hospital):

|

|||||

Figure 9 (Schreiner & Aanderud, 2008, s. 17)

Standard marine communication phrases

A1/1.3 - Requesting Medical Assistance

Exercise:

Info sheet and mini-presentation

The info sheet must show or explain the most essential information, and include easy reference (links preferably) to where to get additional info.

The mini presentation is a short (four-five minutes) explanation of the subject using the info sheet.

- General first aid principles aboard.

- Basic anatomy for the first aider.

- Cuts and severe bleeding.

- Hand and foot injuries.

- Burns and scalds.

- Head injuries and eye injuries

- Shock.

- Hypothermia and near drowning.

- Radio medico and external assistance.

SMCP: A1/1.3 Requesting Medical Assistance

Must include the following:

What is it? Definition if needed.

How do you get it? Situation etc.

What to do? Immediately – observation – evacuation?

Glossary

The skeletal system

| English | Norwegian |

|---|---|

| Cranium | Kraniet |

| Parietal bone | Issebein |

| Occipital bone | Bakhodebein |

| Mandible | Kjevebein |

| Clavicle | Kragebein |

| Sternum | Brystbein |

| Scapula | Skulderblad |

| Xiphoid | Brystbeinstapp |

| Vertebral column | Ryggrad |

| Ilium | Tarmbein |

| Sacrum | Korsbein |

| Coccyx | Halebein |

| Humerus | Overarmsbein |

| Radius | Spolebein |

| Ulna | Albuebein |

| Carpals | Håndrotsbein |

| Metacarpals | Mellomhåndsbein |

| Phalanges | Finger-/tåbein/falanger |

| Femur | Lårbein |

| Patella | Kneskål |

| Fibula | Leggbein |

| Tibia | Skinnebein |

| Tarsals | Ankelbein |

| Metatarsals | Mellomfotsbein |

The muscular system

| English | Norwegian |

|---|---|

| Sternocleidomastoid | Skrå halsmuskel |

| Deltoid | Deltamuskel |

| Pectoral | Brystmuskel |

| Trapezius | Kappemuskelen |

| Biceps | Armbøyer |

| Triceps | Armstrekker |

| Rectus abdominis | Rette magemuskler |

| Latissimus dorsi | Brede ryggmuskel |

| Gluteus maximus/medius/minimus | Setemusklene |

| Quadriceps | Knestrekker |

| Rectus femoris | Rette lårmuskelen |

| Sartorius | Skreddermuskel |

| Biceps femoris (hamstring) | Knebøyer (hamstring) |

| Tibialis | Fremre leggmuskel/ankelbøyer |

| Gastrocnemius | Tohodet tykkleggsmuskel/ankelstrekker |

| Achilles tendon | Akillessene |

The respiratory system

| English | Norwegian |

|---|---|

| Pharynx | Svelg |

| Tongue | Tunge |

| Larynx | Strupehode |

| Trachea | Luftrør |

| Bronchus | Bronkie |

| Bronchiole | Bronkioler |

| Pleura | Lungehinne |

| Alveolus | Alveoler/luftblære |

Organs of chest and abdomen

| English | Norwegian |

|---|---|

| Thyroid gland | Skjoldbruskkjertelen |

| Windpipe | Luftrør |

| Oesophagus | Spiserør |

| Lung | Lunge |

| Heart | Hjerte |

| Spleen | Milt |

| Liver | Lever |

| Kidney | Nyre |

| Gall bladder | Galleblære |

| Stomach | Magesekk |

| Colon/large intestine | Tykktarm |

| Small intestine | Tynntarm |

| Caecum/appendix | Blindtarm |

| Ureter | Urinleder |

| Bladder | Blære |

Conjunctions and transition words

Many of the texts and reports you will be writing in English will require you to use a more advanced form of the language than you have possibly done earlier. This means that you will have to present and discuss many ideas in one text. In order to do this, you will have to use conjunctions and transition words. Conjunctions and transition words allow the writer to reinforce ideas with additional information, present alternatives in a discussion, give conditions, emphasize an idea, give examples, present cause and effect, and describe a chronological sequence of events.

Even if you are not familiar with the terms conjunction or transition words, you have more than likely used them. Conjunctions do exactly what their name says- conjoin ideas. Some of the most common conjunctions are known as coordinating conjunctions, and are easily remembered through the following acronym:

| F or | The rescue was a success, for all passengers were present on land. For introduces phrases of explanation, much like the transition word because. |

| A nd | Oil tankers are subject to special regulations, and they must have a double bottom. And adds ideas. |

| N or | The Captain was not allowed to work on the ship nor was he allowed to sail for the company again Nor adds ideas in a negative sentence. |

| B ut | Mooring operations are difficult, but they can be managed with good procedures. But connects contrasting ideas. |

| O r | There are guidelines instructing when heavy fuel oil or diesel fuel should be used. Or gives alternatives. |

| Y et | Heavy weather had begun, yet the crew continued their work on deck. Yet functions much the same as nevertheless. Both present a contrast or an exception to the other statement it joins. |

| S o | Many ships were entering the canal, so the supertanker was forced to wait. So shows consequence. |

You may have noticed that only some of the sentences above have commas. This is because a comma is necessary only when joining complete sentences together. A complete sentence requires both a subject and a verb.

Example:

The First Mate attempted contact with the oncoming vessel. The oncoming vessel responded over the VHF.

Both of the sentences above work well on their own. However, it is perfectly acceptable to join them together.

The First Mate attempted contact with the oncoming vessel, and the oncoming vessel responded over the VHF.

If a sentence is incomplete, it is called a phrase. Joining a phrase to a complete sentence does not require a comma because the phrase cannot function alone.

Example:

The Bosun broke his arm. Was sent to shore.

Was sent to shore is a phrase because it is without a subject (who or what was sent to shore?) and is considered incorrect if left as it is. It can either be made into a complete sentence:

The Bosun was sent to shore.

Or it can join the sentence that came before it:

The Bosun broke his arm and was sent to shore.

As you can see above, a comma is not used.

You are familiar enough with the English language to know that there are many different ways to say the exact same thing. Having a broad vocabulary and the ability to pick from a variety of words can add life to your writing and make it more interesting for the reader. One way to do this is through the use of transition words and phrases. Transition words and phrases have the same function as FANBOYS, but some of the words and phrases can give the statement they are used with a different meaning.

The chart below gives some examples of common transition words and conjunctions along with when they are used.

| Purpose | Example words and phrases |

|---|---|

| Adding ideas | Additionally, in addition, furthermore, moreover, too, as well as, and |

| Putting ideas in a sequence or chronological order | Firstly, secondly, thirdly, prior to, meanwhile, during, after, later, till, at the present time, to begin with, as soon as, as long as, next when, before, whenever, eventually, by the time, whenever, instantly, immediately, quickly, occasionally, presently, suddenly, finally, afterwards |

| Emphasize and support with examples | Such as, namely, with attention to, even, indeed, in fact, of course, notably, for example, for instance, to clarify, in particular, usually |

| Consequence | As a result, therefore, so, as a consequence, in that case, because, consequently, for this reason, accordingly, because, which |

| Opposition or contradiction | In contrast, in spite of, on the contrary, on the other hand, even so, though, nevertheless, nonetheless, conversely, although, however, in reality, although this may be true, despite |

| Conclusions | On the whole, to conclude, in conclusion, to sum up, in brief, thus |

Comma use can be tricky when using transition words and phrases, but there are some general rules that can help you remember when and where you should use a comma. Check out chapter x for more information on comma use.

- If you start a sentence with a transition word or phrase, a comma is necessary.

The ship arrived at port before schedule. However, the cargo was not ready for loading.

- A comma is not needed when connecting two phrases (incomplete sentences) with a transition word or phrase.

The crew was prepared in spite of the delays.

Exercise

1. Identify the conjunctions and transition words and phrases in the following incident report taken from The United States National Transportation Safety Board.

Edited:

https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Pages/MAB1808.asp

2. Re-write the following sentences using transitions words and phrases.

a. Engine breakdowns can be expensive. Proper maintenance routines are important.

b. The AB was gravely injured. He had followed the correct mooring procedures.

c. Vessels that are under way in heavily trafficked fairways must be careful. SOLAS and COLREGs have strict requirements about lookouts in these situations.

d. Paperwork and documentation are a major part of an officer's daily work. There will be less time for other important jobs and responsibilities.

e. There are many regulations regarding passenger safety on cruise ships. All passengers must undergo a muster drill within 24 hours after their embarkation.

Bibliography

- Schreiner, A., & Aanderud, ,. L. (2008). Medicine on Board. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- St. John Ambulance . (n.d.). The recovery position . Retrieved from http://www.sja.org.uk : http://www.sja.org.uk/sja/first-aid-advice/first-aid-techniques/the-recovery-position.aspx

- Ulven, A. J. (2017). Radio Medico: Be prepared when calling the doctor. Navigare, 2017(1), pp. 46-47.

- WHO. (2007). International Medical Guide for Ships (3rd edition ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.