Chapter 3: How to build a ship

In this chapter you will ….

- get a short historical background

- learn about some of the jobs in a shipyard

- have a look at some rules about the construction of ships

- see how ships are categorized based on size

- learn what classification and classification companies are

- learn about laws and vocabulary regarding ship measurements

- read about how to search online

- get some tips and tricks when it comes to giving a presentation

The Norwegian Tradition

Petroleum engine for ship from 1893/94. Source: Norsk Teknisk Museum

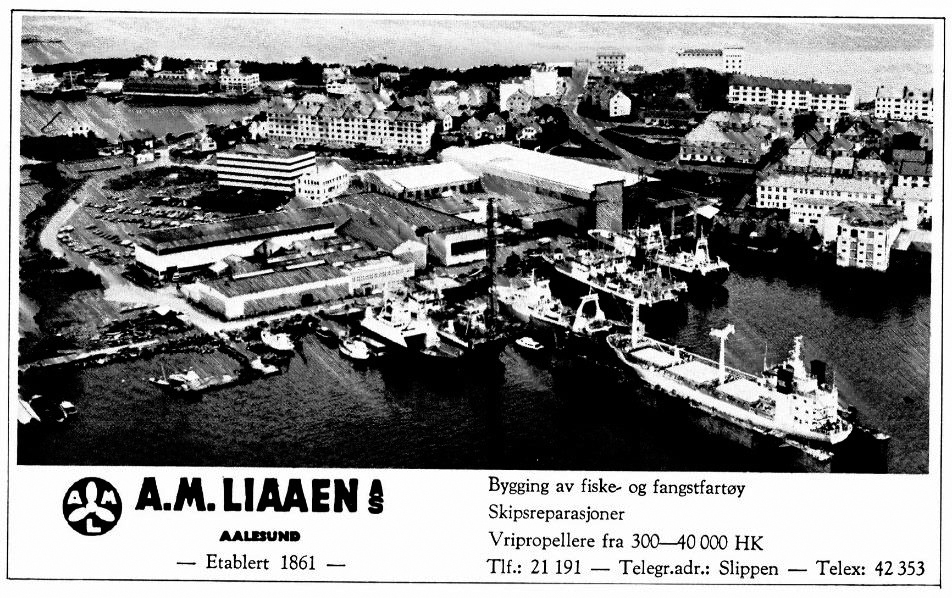

Norway has a long and proud history when it comes to shipbuilding. We have already mentioned the Vikings and their ships; let us fast forward about 1,000 years and see how shipbuilding has changed over the last century. We start with a trip down memory lane in Ålesund, where one of the largest and eldest shipyards was situated. A.M. Liaaen was founded in 1861, then called Ystenes Skibsværft, and quickly became one of the leading shipyards both locally and nationally. The years from 1890 to 1908 saw 53 ships built; among them Leiv Eriksen, the first ship with a shelterback / watertight deck and engine in Norway.

After some turbulent years following the Ålesund fire in 1904 and the recession after World War I, the shipyard only took on repairing, overhauling, and rebuilding until they bought the competitor Aalesunds Mekaniske Verksted, situated on Kvennaneset, in 1927. Managing the company at that time were two young brothers; Nils J. who was 25 years old and Adolf, who was only 21! Quite a task to take on, don't you think? They managed it well, though, and earned a good reputation.

The building of Trio at the first shipyard on Ysteneset. If you want to read about the building of a true copy of this "bankskøyte", you can visit bankskoyta.no

Much of the work done in most shipyards those days had to do with fishing, which made them vulnerable for the whims of nature. From about 1927 to 1939, the fishery for cod almost halved, leaving the investment appetite low among those buying services from Liaaen. Nils put his mind to finding other sources of work and ended up with a rather profitable production of mechanically driven trawl winches. The visionary Nils J. Liaaen also saw the need for diesel engines on board fishing ships if they were to sail all the way to the fishing grounds in the areas around Iceland and Greenland without having to refuel. In 1938 A.M.Liaaen could proudly mount the first Norwegian constructed and produced two-stroke diesel engine in MS Aalesund; which also was built at Liaaen shipyard. Unfortunately, the production of two-stroke diesel engines only lasted up until right after World War II when the government allowed the import of cheaper, foreign engines. New ideas had to be thought, and the always-inventive Nils set his mind on propellers.

Fun fact

During the war, Liaaen was "appropriated" by the Germans. They were still allowed to do business, but at the mercy of the Germans, and with German foremen on the work site to ensure work being done in at a pace that was acceptable for the Wehrmacht. This was not an easy task, as the Norwegian workers tried their best to do as little as possible as slowly as possible; blaming late deliveries, wrong dimensions, or not enough material to be useful. One day, a German patrol boat came to the shipyard to have a damaged propeller repaired. The ship was placed in the slipway and a new piece was welded on, customized and grinded. What the German foreman did not know, was that the boss himself; propeller constructor and engineer, Nils J. Liaaen, had told his workers to weld the new part of the propeller with a wrong angle, without being noticeable. The patrol boat went from the shipyard and out through the strait without problems, but as they reached the Valderhaug fjord and increased the speed, an intense vibration was felt in the stern. The propeller fell off and disappeared in the ocean, leaving the Germans with no evidence to back up their theory of sabotage from the shipyard.

Another story from Liaaen's history is when MS Fru Inger grounded one winter night in 1953, resulting in severe hull damage. The propeller blades also came in contact with the seabed and were severely damaged. The pitch propeller hub and inner parts were, however, found good because of Liaaen's patented pitch propeller plant construction "progressive strength". Because of this design, the sequential order of damage was 1) propeller blade, 2) propeller hub with internals, and 3) propeller shaft and gear.

Liaaen and propellers soon became one and the same. Their pitch propellers even made headlines internationally, but the wealth of international private competitors presented a problem for Liaaen. The answer was manufacturing under license; both with national and international companies. This kept the Liaaen name in the propeller industry without the risk of losing a lot of money.

Shipbuilding in Norway

The Norwegian shipbuilding industry was characterized by large yards in the larger cities, but this picture changed. The shipping and oil crisis in the 1970s led to altered markets for the construction of new ships, and until the mid-1980s there was a drastic redevelopment in the shipbuilding industry across most of the western world. In Norway, the crisis led to more shipyards, especially the largest ones, shifting production from shipbuilding to offshore. Norwegian shipbuilding industry lost its leading position on an international scale, while countries such as Japan, South Korea, Germany, Italy, China, and Poland became the world's largest in shipbuilding. Today, Norwegian shipyards are typically small or medium-sized and located in smaller but significant industrial areas along the Norwegian coast.

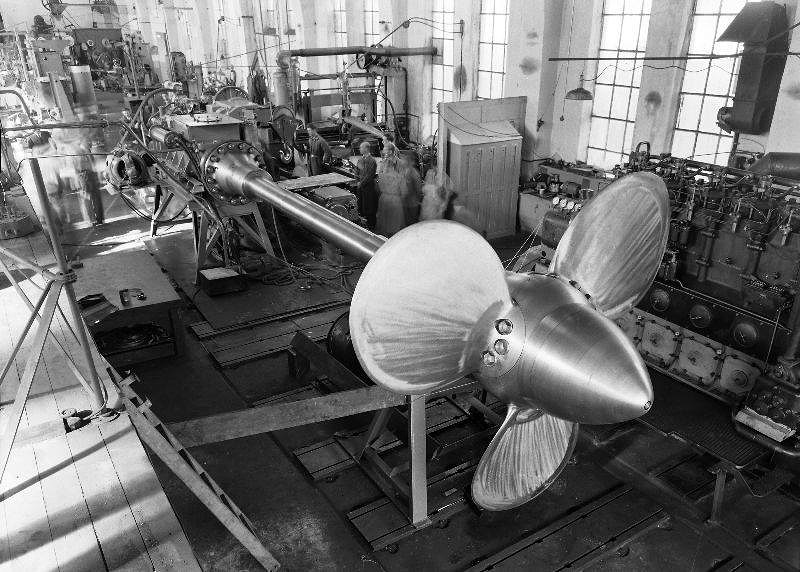

Source: Martin Mongiello

Here, the yards are the linchpins of the industrial environment that is the origin of the concept the maritime cluster. In recent years, the reorganization has resulted in an offshore industry that is both a competitive and a technological leader. (SNL, 2015) The recession around 1990 took its toll, and many of the century-old shipbuilding companies went bankrupt or had to cut in their workforce; the trade was left crippled and scrawny. In 2008, there were around 50 shipyards in Norway, with a workforce of approximately 4,500 employees, delivering a total of 75 ships a year.

The Norwegian Shipyard Association reported a moderate order intake in 2017. 19 commissions had been entered into contract at Norwegian shipyards before August, each of which has a value of more than NOK 50 million. In total, they have 19 vessels worth 7.5 billion, which is a significant increase from the same period in 2016. (Skipsrevyen, 2017)

Moving the Industry Abroad

Economy is always a factor, and for the Norwegian maritime industry, this has influenced both the people building the ships and those working on board. Replacing the Norwegian sailor is a topic for another chapter, so for now we will take a closer look at how the work done at the shipyards has changed over the last few decades.

Earlier, the entire shipbuilding process, from idea to launch, was completed by one company. The shipyards had numerous employees in all kind of departments; engineers, economists, welders, electricians, and more; all playing their important part in the process. A town with a shipyard was a prosperous one! Unfortunately, competition with the shipbuilding industries in countries with lower labour costs put an end to this long-standing tradition, causing the Norwegian shipyards to lose their place in the market in the last decades of the twentieth century. Fortunately, they are still involved in the construction of specialized ships in, for example, the oil and fishing industry.

Photo: Dan Christer Virak

Where did the industry move when it failed in Norway, then? The answer is complex, actually, seeing that some of the Norwegian shipbuilders did not completely get out of business. Some of them managed to keep parts of their industry intact, building the hull abroad while doing the installation work "at home". The main competition, and contractors, was with the earlier communist countries in Europe. This meant shorter distances both for surveyors for the shipbuilders and for towing the hulls from the contractor to the Norwegian shipyard.

The picture is from an article in Poland@sea and shows the first three hull sections under tow. Read the article to learn more and answer the questions below.

Exercise

- Who is the owner of the ship?

- Who has designed the ship?

- Where were the sections built?

- How does the cooling unit work?

- Use your own words to describe how the sections were towed to Flekkefjord.

Who works at the shipyard?

Building ships is a complex engineering process; the process of shipbuilding is an accumulation of ideas and inputs from professionals spanning a wide range of specializations.

Welders are welding metal structures such as the ship's hull plates, frames, girders, tanks, foundations, and pipes. They perform all types of welding that is required in the shipyard, like Arc welding, MIG welding, and TIG welding. Solderers are also used, but since soldering is a minor job in the entire workflow, subcontractors often get the soldering work. Read more about Arc welding, MIG welding, and TIG welding.

Structural Fabricators read the engineering drawings and do the fabrication of metal jobs. They also install the fabrication on the hull. You can read more about the exciting future for structural fabricators here.

Plumbers: Piping in ships involves being able to read and understand isometric piping layout drawings and Piping and Instrumentation drawings (P&IDs). Not only are these plumbers specialized in the installation of all pipelines inside a ship, but also all kinds of pipefittings like valves, and flanges. As an engineer, you will have to know some of these things; check out this page to learn more.

Electricians: There are many electric cables on board the ship, and the electrician needs to be able to read the cable routing plans to know what to put where. Their work includes installing all the electrical and electronic equipment, the navigational equipment in the bridge and radar, lighting, control panels, main electrical control room panels, and even more. A necessary skill for electricians is the ability to identify colours, so naturally this is not a job for those with colour blindness.

Carpenters: Wooden ships are not often built these days, but carpenters are still required at a shipyard. The carpentry department prepares the wooden templates for the ship's hull, which are used for bending the straight metal plates to the required shape. They also prepare templates for sea pipes and build dock blocks and keel blocks required for dry docking and ship launches. In the future, we will see more modern measurement methods, e.g. 3D laser scanning. Check out what Lobna Abdelaziz from the United Arab Emirates has to say about 3D laser scanning in this article.

Riggers have a variety of jobs at a shipyard- everything from lifting and shifting heavy structures, scaffolding to moving moderate weight structures within the shipyard and operating various types of cranes. They are trained to use hand signals to communicate among themselves and the crane operator during lifting and shifting operations that create loud noise.

Quality Control Inspectors: A QC Inspector is one of the most skilled among the workforce in a shipyard. They are responsible for tests on weld joints, dimensional control inspections of major structures, and much more. The design drawings are used as a reference for checking dimensions, and record keeping is critical for the inspector. The records must be compiled and maintained as the hull is built, in order to document that required testing and inspections were successfully accomplished. The true "final inspection" is during the sea trial period where the ship is put through planned tests while underway to confirm operation and safety of the crew during actual conditions, including hard turns and emergency stop demonstrations. (Halverson, 2010)

Supervisors: Often, workshop level departments have their own supervisors. For example, a hull supervisor typically looks after all the aspects of structural outfitting on the ship. Similarly, there are supervisors for each department, for example, Piping supervisor, Electrical supervisor, Rigging supervisor, Maintenance supervisor, Drydock supervisor, etc. Usually, the most skilled and experienced among fabricators, fitters, electricians, plumbers, etc. are promoted to supervisor.

Building a society

All the shipyard workers need a place to live, and more often than not they have families. Below, you can see the area of Liaaen in Aalesund over a period of about 85 years.

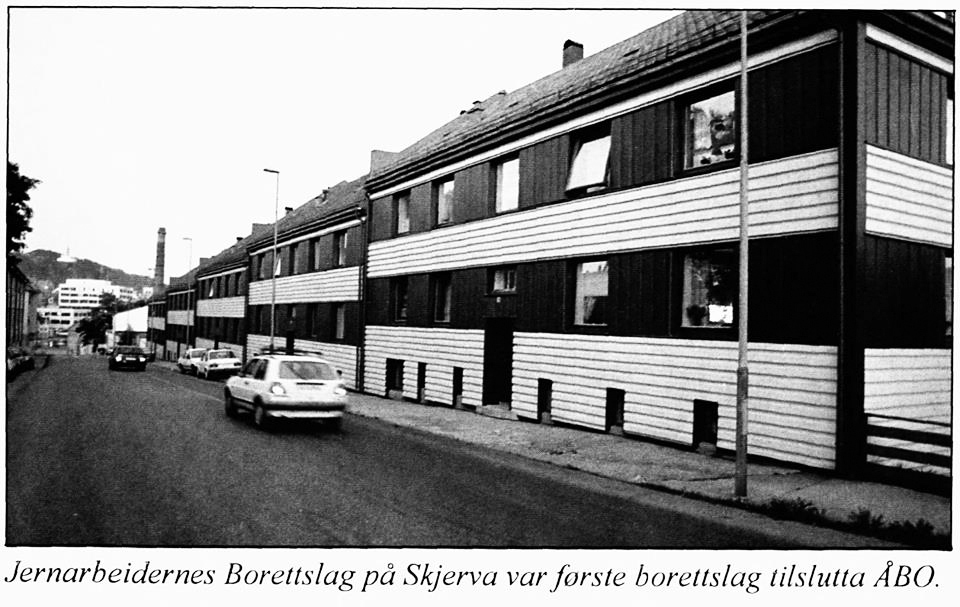

This is the area of Steinvågen where Kvennaneset is situated. This picture is from 1936, and the shipyard is already quite large. On the right side of the picture you can see the first block of flats made to house the workers and their families.

This newer picture shows some of the housing up close. These buildings are the same as the ones you can see to the right on the above picture.

The area is growing. We are now in the 70s and can see several new blocks of flats in vicinity of the shipyard.

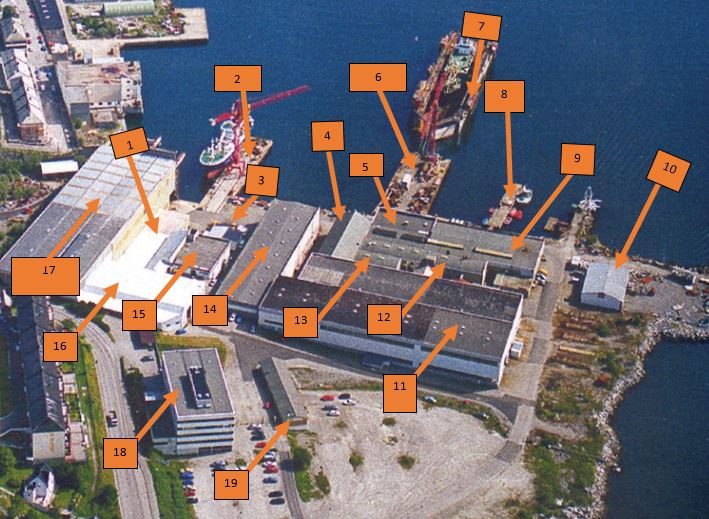

From 1998, the shipyard was reduced to being a repair yard, and in 2003, it was closed down for good. This picture from 1999 gives you a good overview of all the buildings built over the years. These buildings include both housing for the workers and all the shipyard buildings in a shipyard that, at its most prosperous, employed over 600 people .

This is Steinvågen in 2017. The shipyard is now inhabited by Aspevågen Marina

Ship building from A to Z

A shipyard consist of many types of workers and also a lot of different buildings. The picture below is an extract from the picture Steinvågen 1999 you saw in the text about building a society.

The buildings have been named with help from Cato Malmedal, a former worker at Liaaen and now the owner of Aspevågen Marina.

- Intermediate building/Pipe workshop

- North quay

- Electrical workshop

- Engineering shop, old part

- Quay office

- South quay

- Floating dock

- Barges

- Pipe workshop and outdoor machinery

- Spray painting and sandblasting

- Assembly hall

- Engineering shop, propeller department

- Tool room

- Pipe and iron stockroom

- Stockroom

- Sheet-metal workshop

- Slipway and sheet-metal hall

- Officebuilding

- Annex office building

In addition, the area also had a welding school and a workshop for prefabrication of pipes.

Meanwhile in Asia...

Let us visit a shipyard far from our home shores; click the links to visit Sanoyas Shipbuilding Corporation at the Mizushima Shipyard and the Osaka Shipyard in Japan.

For a brief and helpful explanation on the process of building a ship, click this link from Sanoyas.

Ship design

Shipyards build ships in all sizes; from the smallest fishing boat to the largest crude carrier. The purpose of the ship and where it is going to sail limits the designers when it comes to structural design.

Construction of ships

Rules and regulations are many when it comes to the construction of ships. We will focus on the legal aspect regarding the bottom and bulkhead structure in the following.

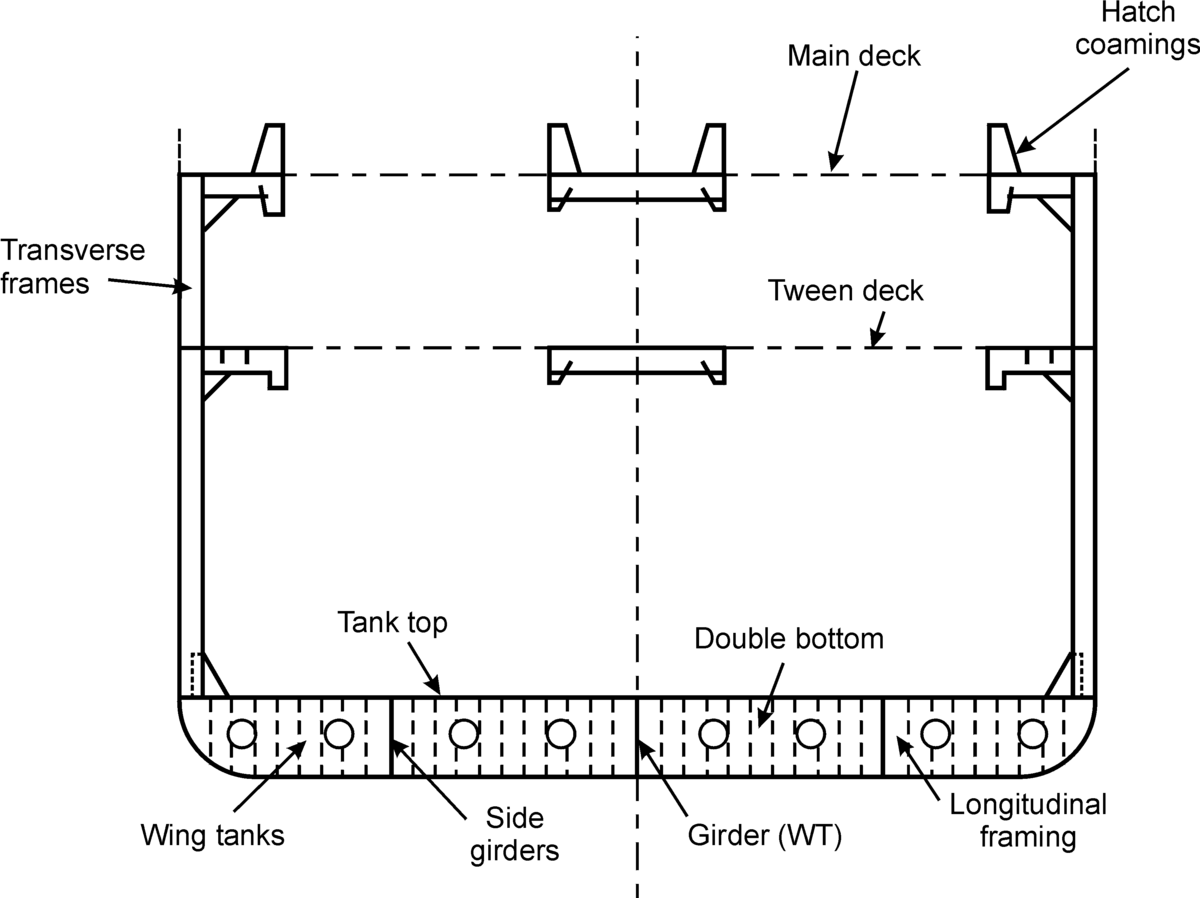

The bottom structure

(Source: Wikimedia)

Single bottom is usually found on smaller ships as they do not carry heavy cargo. Alternatively, double bottom ships are built with two complete layers of watertight surface. Historically, fuel or ballast water have been stored between the two bottoms, but MARPOL put a stop to fuel storage with amendments to Annex 1. The official name of this is RESOLUTION MEPC.141(54) (adopted on 24 March 2006) AMENDMENTS TO THE ANNEX OF THE PROTOCOL OF 1978 RELATING TO THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION FOR THE PREVENTION OF POLLUTION FROM SHIPS, 1973 (Amendments to regulation 1, addition to regulation 12A, consequential amendments to the IOPP Certificate and amendments to regulation 21 of the revised Annex I of MARPOL 73/78). Just reading the title of IMO documents can dishearten any reader! Remember that if you dismantle the sentences, it will be easier to get the "real meaning".

Exercises

-

Try to find out what IMO says about regulations of the bottom structure when it comes to fuel storage in the amendments to Annex 1.

Learn how to use the search engine in pdf-documents. -

Visit dieselship.com to learn useful words about double bottom constructions.

Open this document and put all the words in their correct place. Translate the words into Norwegian.

Additional reading

Additional reading: Designing A Ship's Bottom Structure – A General Overview.

(Source: Wikimedia)

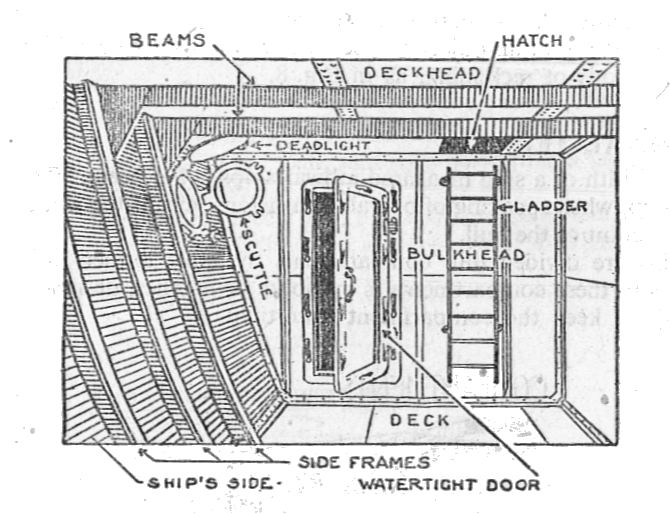

Bulkheads are designed to carry out different functions; the main purpose is to create compartments. In addition, bulkheads provide structural stability and rigidity to the ships, minimize the forces acting on the ship due to waves, restrict the passage of flame, and prevent water from entering different parts of the ship in case of a flooding.

The purpose of the ship determines what kind of bulkhead is used.

Additional reading

Additional reading: Understanding Watertight Bulkheads In Ships: Construction and SOLAS Regulations

Exercise

- Watch the video [Kleven - the building of build no 386 for Maersk Supply Service]

-

Write a narration for the building of number 386 as seen in the video.

-

Record yourself reading your text.

Ship types

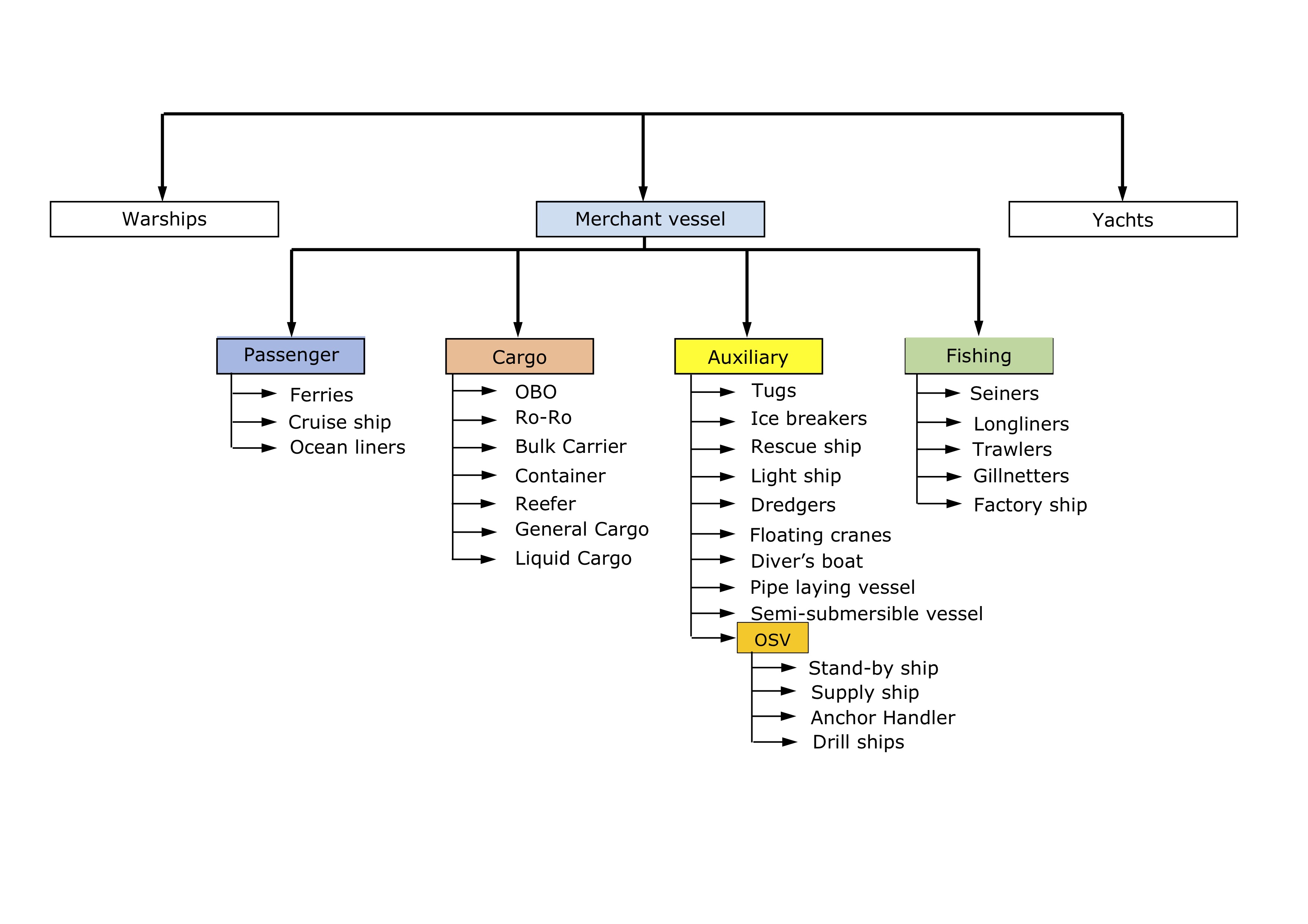

In chapter 2, we looked at different ship types. Below you can see a short summary.

Exercise

Which one do you think could be your ideal workplace?

Write a short text where you state the reasons for your choice.

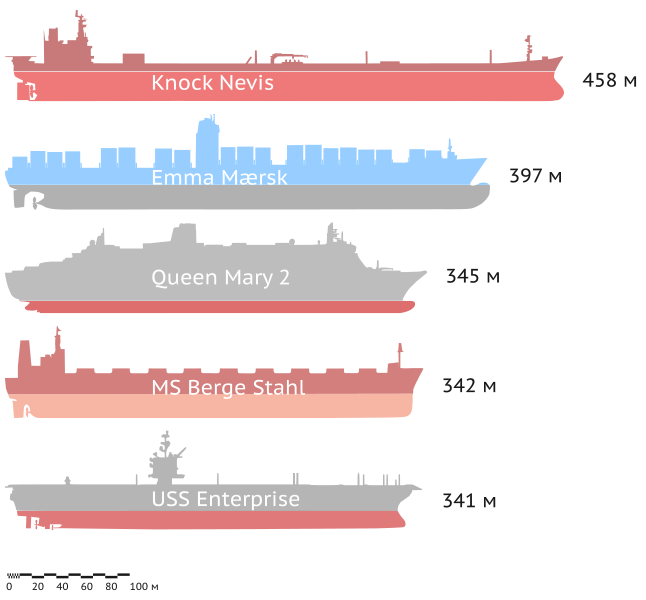

Ship sizes

(Source: Wikimedia)

Think about the ship or ships you have previously sailed on. Was it a giant tanker or a medium sized offshore service vessel? There is no end to the different sizes of ships that can be found sailing today. From the world’s largest cruise ship to the smallest fishing trawler, ship sizes vary to suit their individual purposes.

Maritime Connector and Marine Insight both present categories of ships based on their size.

Exercise

Read the two sites mentioned above, choose one of the ship categories and make your own description from what you have learned.

Tell a tale

Ever wondered about being part of a team at the shipyard when they are building a new ship? Below you can read the thoughts of Johnny Træet, a Norwegian engineer, who has done just that.

Building a ship

At some point during your career, you might get lucky and get an opportunity to be part of a team that supervises shipbuilding. Moreover, you could get the chance be team leader and responsible for building a ship. You would be the owner’s on-site representative for your department, but during the building of a new ship, departments have a tendency to overlap, possibly giving you responsibility for other departments as well.

Being part of a team like this is a great opportunity to «boost» your career since you will be learning a lot about how a ship functions faster than if you were not part of such a project. A major part of this job is networking and building relations between your company and the shipyard, as well as between your own department and equipment suppliers. You will also learn the importance of good human relations, and, if you are successful, many companies will want to hire you.

Very often, you will find that being a diplomat is better than being right. Many people seem to forget that the ship is the shipyard’s property until the handover, and equal respect for all the workers involved are crucial. The most important thing to remember is that everybody is important, from the welders and cleaners to the foremen.

So, what does it mean to be a supervisor? To be a supervisor means that you must check all drawings, piping and equipment for your department, and work together with other supervisors when things are crossing into your department. You must carry out team meetings; have meetings with representatives for the shipyard to correct faults and keep the company informed about the progress and any changes that are being made. Furthermore, changes must be approved before they are carried out on the ship, and you must inform both your company and the shipyard management about these matters. Supervising also means to guide the foremen so they understand how you want to address the tasks and how you want the end result to be.

Sometimes the ship is built in a foreign country and as an added bonus, you get to learn about other cultures and see new places. Overall, it is very interesting to be part of a team like this, and it is highly recommended if you get a chance to join in.

What is the role of the Classification companies?

Short historical background

©Lloyd’s Register Foundation

The origin of classification is associated with the Lloyd's Register of Shipping. It was customary in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries for merchants, shippers and underwriters to meet in coffee houses in London to discuss business. Lists of ships were circulated in those establishments, and these lists were particularly useful in providing underwriters with information about the degree of risk involved in insuring the ships and their cargoes. One of the coffee houses was owned by Edward Lloyd, a renowned entrepreneur. Lloyd made history when he provided a list or bulletin about ships in 1702. Known as Lloyd's List, such lists have continued to be published. (Chowdhury, 2015)

Several classification companies were founded in the following years. Among the most important are Bureau Veritas in 1828, Registro Italiano Navale (RINA) 1861, The American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) 1862, Det Norske Veritas (DNV) 1864, Germanischer Lloyd (GL) in 1867, Nippon Kaiji Kyokai (ClassNK) 1899, and The Russian Maritime Register of Shipping (RS) in 1913.

What is classification?

Read Infosheet no.35 from Lloyd's Register of Shipping for a concise and informative explanation of classification.

Over 90% of the world's merchant shipping tonnage is classified by the 12 member societies of the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS). The following paragraphs are from IACS; check out this file if you want to read more.

The role of classification and Classification Societies has been recognized in the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, (SOLAS) and in the 1988 Protocol to the International Convention on Load Lines. The IACS can trace its origins back to the International Load Line Convention of 1930 and its recommendations. The Convention recommended collaboration between Classification Societies to secure "as much uniformity as possible in the application of the standards of strength upon which freeboard is based…".

A second major Class Society conference, held in 1955, led to the creation of Working Parties on specific topics and, in 1968, to the formation of IACS by seven leading Societies. The value of their combined level of technical knowledge and experience was quickly recognised. In 1969, IACS was given consultative status with the International Maritime Organization (IMO). It remains the only non-governmental organization with Observer status which is able to develop and apply Rules.

Scope of classification

Implementing the published Rules, the classification process consists of:

• A technical review of the design plans and related documents for a new vessel to verify compliance with the applicable Rules;

• Attendance at the construction of the vessel in the shipyard by a Classification Society surveyor(s) to verify that the vessel is constructed in accordance with the approved design plans and classification Rules;

• Attendance by a Classification Society surveyor(s) at the relevant production facilities that provide key components such as the steel, engine, generators and castings to verify that the component conforms to the applicable Rule requirements;

• Attendance by a Classification Society surveyor(s) at the sea trials and other trials relating to the vessel and its equipment prior to delivery to verify conformance with the applicable Rule requirements;

• Upon satisfactory completion of the above, the builder's/shipowner's request for the issuance of a class certificate will be considered by the relevant Classification Society and, if deemed satisfactory, the assignment of class may be approved and a certificate of classification issued;

• Once in service, the owner must submit the vessel to a clearly specified programme of periodical class surveys, carried out on board the vessel, to verify that the ship continues to meet the relevant Rule requirements for continuation of class.

Assignment, maintenance, suspension and withdrawal of class

Class is assigned to a vessel upon the completion of satisfactory review of the design and surveys during construction undertaken in order to verify compliance with the Rules of the Society. For existing vessels, specific procedures apply when they are being transferred from one Class Society to another.

Ships are subject to survey regimes throughout its "lifetime" in order to retain its class. These surveys include the class renewal (also called "special survey"), intermediate survey, annual survey, and bottom/docking surveys of the hull. They also include tailshaft survey, boiler survey, machinery surveys and, where applicable, surveys of items associated with the maintenance of additional class notations.

The surveys are to be carried out in accordance with the relevant class requirements to confirm that the condition of the hull, machinery, equipment and appliances is in compliance with the applicable Rules.

It is the owner's responsibility to properly maintain the ship in the period between surveys. It is the duty of the owner, or its representative, to inform the Society of any events or circumstances that may affect the continued conformance of the ship with the Society's Rules.

Where the conditions for the maintenance of class are not complied with, class may be suspended, withdrawn or revised to a different notation, as deemed appropriate by the Society when it becomes aware of the condition. (International Association of Classification Societies, 2015)

Know the Law

So, where can we find laws and regulations about construction, building and certification of ships? We have learned that classification societies are the ones actually doing this work, and most of the "demands" when it comes to specifications are found in the different standards for certification each society has developed. To find the source for these specifications we have to go to the various conventions and codes sat out by the IMO, such as MARPOL, SOLAS, COLREG, and CSS. In addition, the Maritime Labour Convention regulates seafarers' onboard working and living conditions, such as a safe and secure workplace; fair terms of employment; decent living and working conditions. These range from ensuring a safe and secure workplace, fair terms of employment, decent living and working conditions to social protection such as access to medical care, health protection, and welfare. As an engine officer student, you are going to learn a lot about the different conventions and codes. In this chapter, we will start by taking a look at the vocabulary used for measurements in a ship's design.

IMO conventions

A list of all IMO conventions can be found here.

Ship measurements

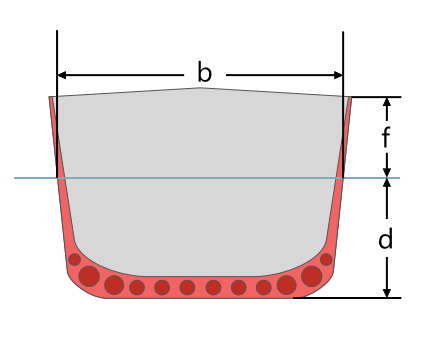

- The beam (b) of a ship is its width/breadth at the widest point as measured at the ship's nominal waterline.

- Draught (d) (draft) is the vertical distance from the bottom of the keel to the waterline.

- Freeboard (f) is the distance from the waterline to the upper deck level.

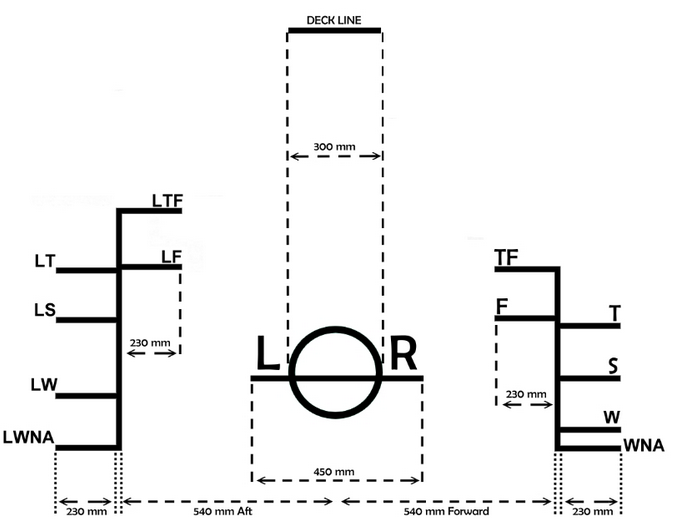

Draught marks are the number markers on each side of a ship. They are placed at the bow, stern, and amidships and indicate the distance from the lower edge of the number to the bottom of the keel or another fixed reference point.

TF – Tropical Fresh Water

F – Fresh Water

T – Tropical Seawater

S – Summer Temperate Seawater

W – Winter Temperate Seawater

WNA – Winter North Atlantic

Prefix L – Lumber

L ⦵ R – Lloyd's Register

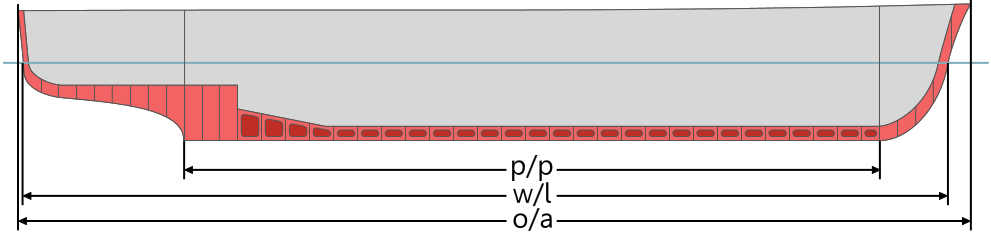

p/p = length between perpendiculars

w/l = length at waterline

o/a = length overall

- Length is the distance between the forwardmost and aftermost parts of the ship.

- Length Overall (LOA) is the maximum length of the ship

- Length at Waterline (LWL) is the ship's length measured at the waterline

- Summer Water Line is the waterline when ship has its standard load.

Tonne, ton, and ton

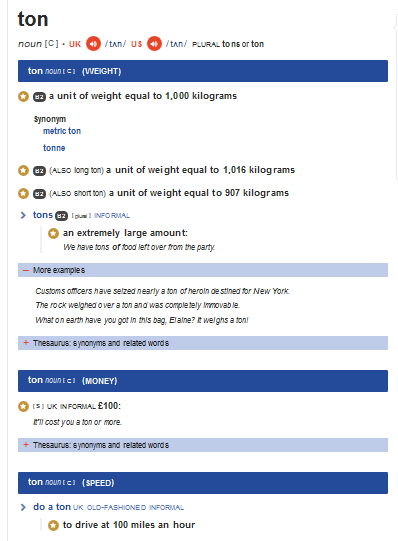

A Norwegian proverb says that a much-loved child has many names. Not only do we have many names when it comes to the abovementioned ton, we actually have many children as well! The picture shows what Cambridge Dictionary says when we search for "ton".

"A ton is 1,000 kilograms" will most likely be the answer if you ask a Norwegian on the street what a ton is. The picture below tells you what you can expect to hear if you ask a Brit or an American. In Australia, they are not quite sure which one they want to use; if you check an Australian dictionary, it will tell you to use the UK-style, but everyday use finds Aussies going with the American definition.

Screen shot from http://www.onlineconversion.com/faq_09.htm

What happens if you ask someone working with ships the same question? The answers will again vary, depending on the native language of the person you ask. However, they will all agree that the term can be used as shipping ton, ocean ton, freight ton, or measurement ton to describe measure of volume used for shipments of freight; the difference appears when you ask them to convert it. In the USA, it is equivalent to 40 cubic feet (ft3) while in the UK it is 42 ft3. In metric measurement, one foot equals 0.3048 meters and one ft3

is 0.0283168466 cubic meters (m3). Luckily, the former difference between the US and the UK measurement foot disappeared in 1959 with the international yard.

Exercises

- How many m3 is 40 ft3 and 42 ft3?

- What is a long ton and a short ton?

- What do we measure in cubic meters / cubic feet?

- What do we measure in liters / gallons?

- What is the difference between UK gallon and US gallon?

So far, so good, but there are even more tons to consider, and let's not forget about tonnage! We start with a register ton, which is used to measure the capacity of ships. One register ton is 100 cubic feet of cargo space; it measures the volume of the ship. A weight ton (W/T) is calculated as a long ton (the British ton = 2,240 pounds = 1,016.04691 kilograms).

Tonnage is the measurement of the cargo-carrying capacity of merchant vessels. It depends on the volume available for carrying cargo. The basic units of measure are the Register Ton and the Measurement Ton. The calculation of tonnage is complicated by many technical factors.

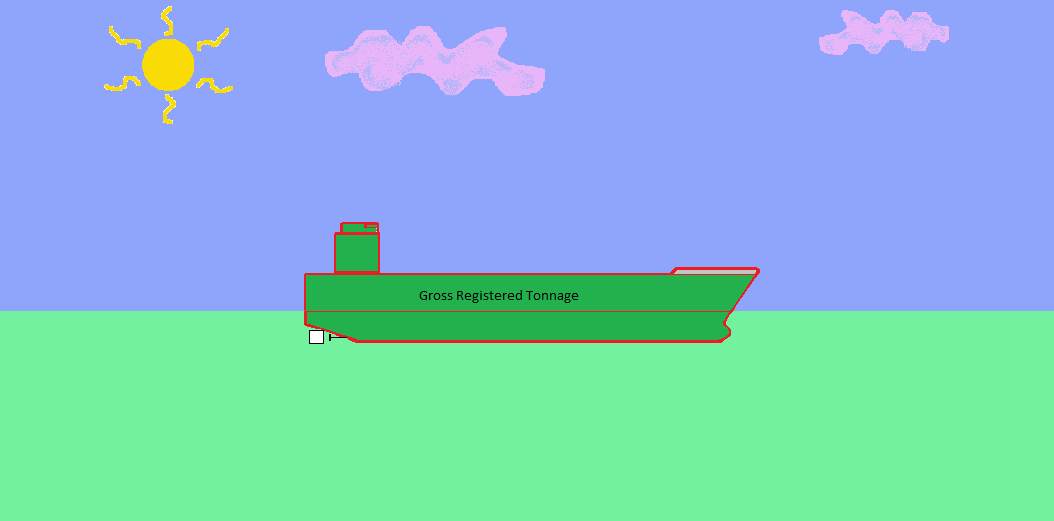

Gross Tons The entire internal cubic capacity of the ship expressed in tons of 100 cubic feet to the ton, except certain spaces which are exempted such as: peak and other tanks for water ballast, open forecastle bridge and poop, access of hatchways, certain light and air spaces, domes of skylights, condenser, anchor gear, steering gear, wheel house, galley and cabin for passengers.

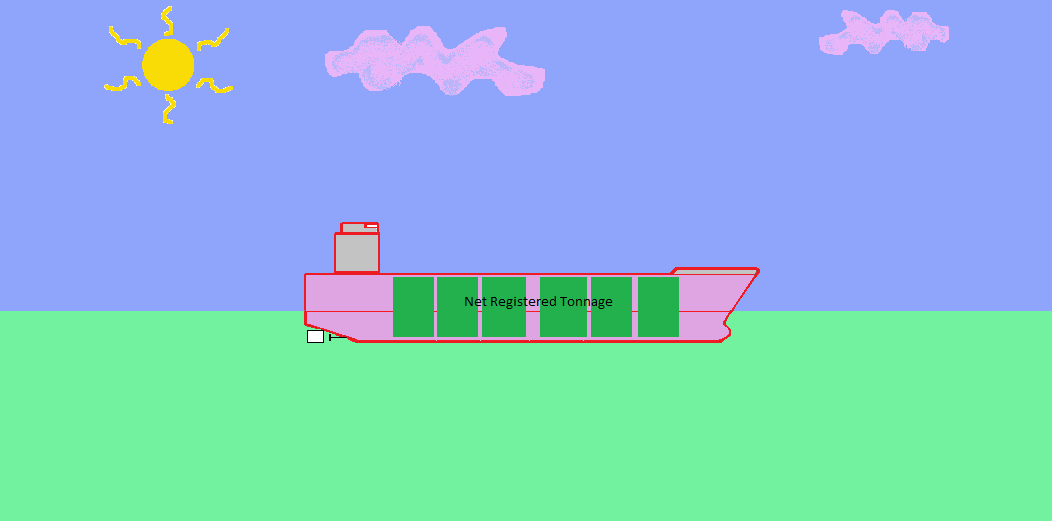

Net Tons Obtained from the gross tonnage by deducting crew and navigating spaces and allowances for propulsion machinery. (Shippipedia, n.d.)

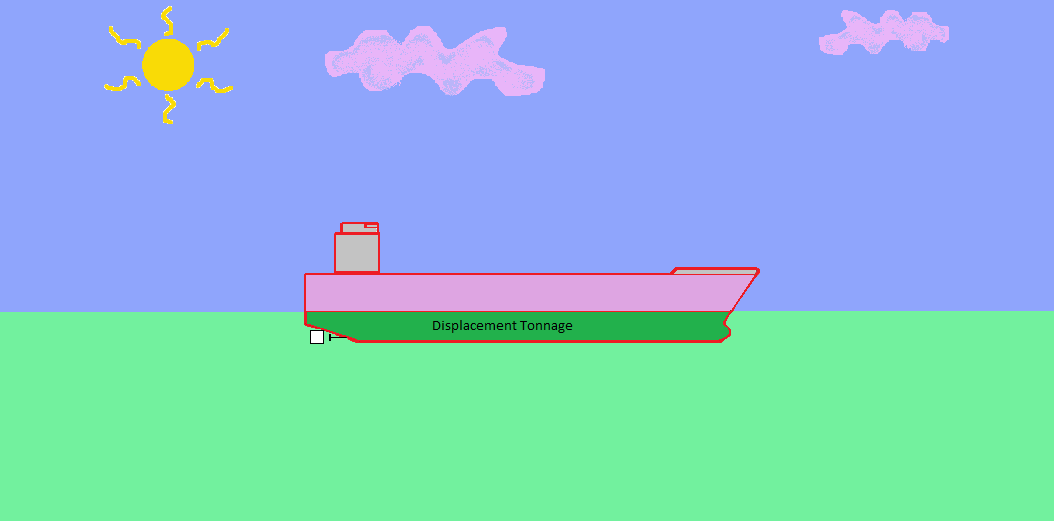

Displacement tonnage is used to define the size of the ship; it refers to the weight of the volume of water displaced by the vessel. If you put yourself in a full bathtub, some of the water inside the tub will spill out on the floor. The weight of the spilled water is equal to the displacement (weight) of the object that took its place in the tub; your body! To determine displacement they start by reading off the draught marks on the vessel. Next, they put the measurements into the ship’s hydrostatic tables that show the displaced volume of water. It is also necessary to know the water’s density to calculate the weight; the density varies with temperature, and seawater is denser than fresh water.

Standard displacement tonnage is displacement tonnage minus the weight of any fuel and potable water carried on board the ship.

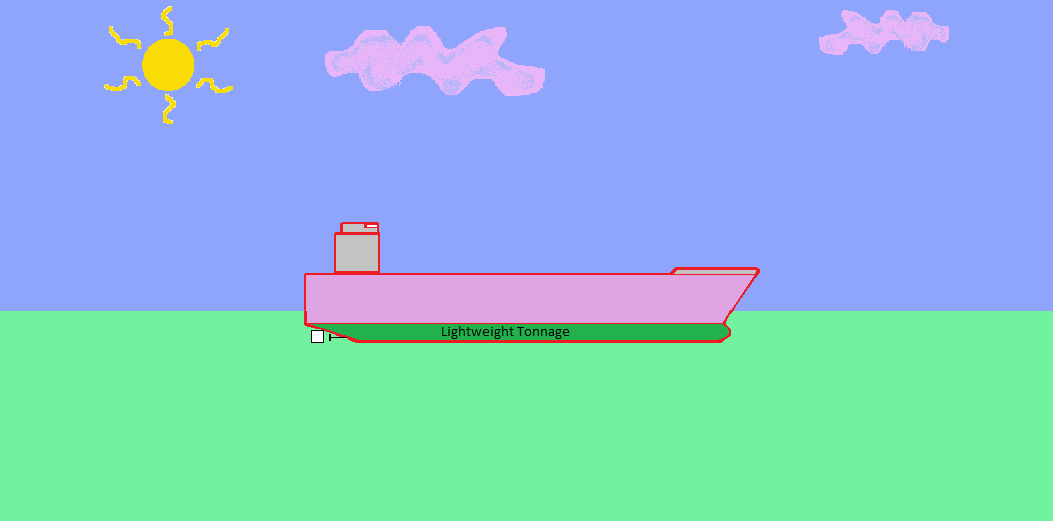

Lightweight tonnage is the weight of the ship itself, including the hull, decking, and machinery, but not including ballast or any consumables, such as fuel, water, oil, and supplies.

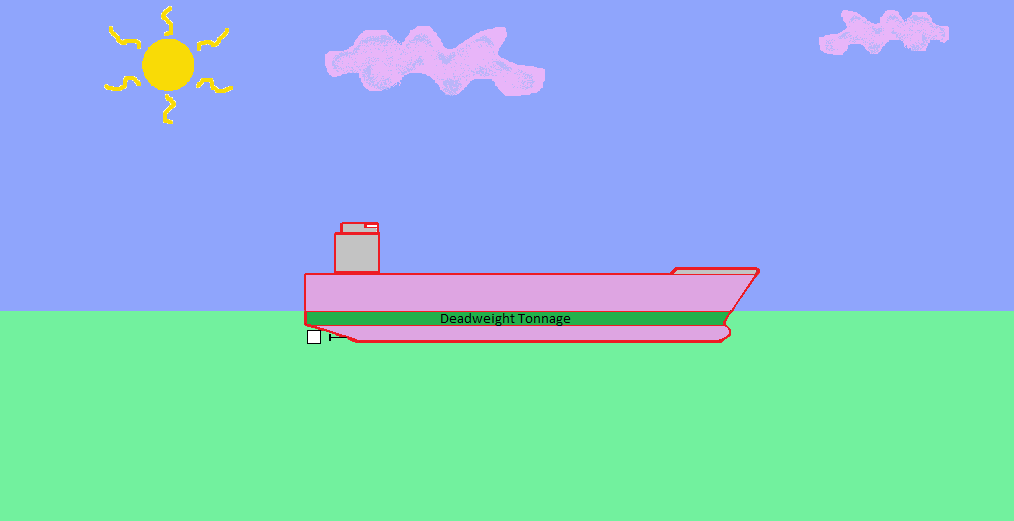

Deadweight tonnage (DWT) refers to the carrying capacity of a vessel. It includes not only cargo, but also the weight of fuel, ballast, passengers and crew, and all of the provisions. The weight of the ship itself is excluded. Deadweight tonnage is the displacement tonnage minus the lightweight tonnage.

Gross registered tonnage (GRT) is a measure of the space available for cargo, crew, passengers, and stores, and is usually the basis for computing drydock charges. Also called gross tonnage. Gross Tonnage or "Gross Tons" is what you will see most often on official ship documents and certificates.

Net registered tonnage (NRT) includes only the volume of actual cargo storage areas; omitting space occupied by the crew, engines, fuel, and navigation equipment. In general, GRT and NRT are in the ratio of 3:2 or, in other words, NRT is roughly equal to 60 percent of GRT. NRT is usually the basis for computing harbour or port charges.

Exercise

The International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969 can be found online at the Faculty of Law at the University of Oslo.

Answer the following questions, using your own words:

- Which ships are an exception from this convention?

- What happens to the certificate if a ship changes flag state? Are there any exceptions from this rule?

- The convention is amendable with specific rules. Mention three of these rules.

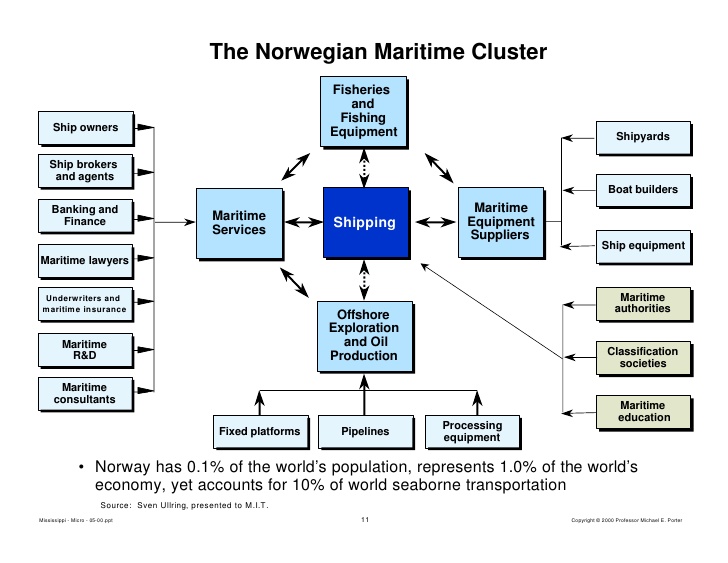

Academic Writing - Using sources

The curriculum for Maritime English and the national assessment criteria both state that a student at maritime vocational colleges in Norway has to, among other things, be able to use information and sources correctly. As you can see from the picture, being critical, accurate, creative, systematic, and showing the ability to analyse and interpret information on a professional level are included as well.

To be able to show your mastery of a topic, it is often useful to find someone to debate with. A debate needs at least two participants, this means you need to find a conflicting opinion to debate with. Find an article online as a source for a different opinion. You can of course use others opinion and knowledge to support your own statements as well.

No matter why you choose to use the words from others, how you do it is important. The most important thing to remember when using anything created by someone else is giving that person credit for their work. Taking someone else's text and presenting it as your own is nothing less than stealing, and stealing is, as you know, against the law. This includes pictures and drawings made by others. Fortunately, there are ways to borrow texts, pictures, and drawings; on the condition that you do it following certain rules.

How to find sources

"Just Google it" is a frequent answer if someone wonders about, well actually, anything at all. However, are we sure we find correct information via Google? Wikipedia is another well-known aid when one will check facts. Both are good, and both have their minefields! Normal people like you and me are the primary sources for whatever is written on the World Wide Web. Are we sure we can trust each other? Let us visit a close relative of the ordinary Google search engine; the omniscient Google Scholar!

Google Scholar's motto is "Stand on the shoulders of giants". Read more about Scholar here; and make sure to check through the different tabs to learn more about how to, among other things, do intelligent searches. Google Scholar is more or less like visiting the library; safer than just asking a random person for the correct answer, don't you think?

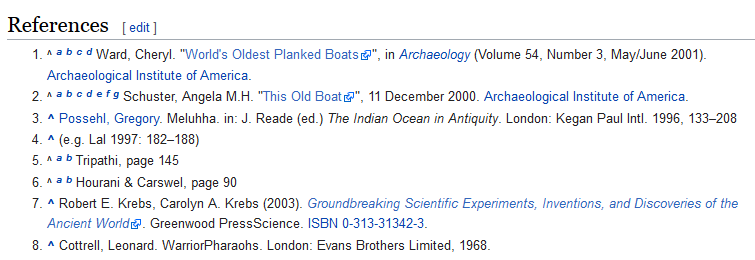

Screenshot from Wikipedia's article on Shipbuilding

Wikipedia is the perfect place to find sources! Most articles are based on facts from somewhere; at the bottom of each article, you find out the wheres and whos. The picture shows the reference sestion of Wikipedia's article on shipbuilding.

In addition to Wikipedia, the Wikimedia Foundation supports a number of free knowledge projects:

- Wiktionary – a free dictionary

- Wikiquote – a free collection of quotes

- Wikibooks – a free collection of books

- Wikisource – a free collection of primary source materials

- Wikimedia Commons – a free media repository

- Wikispecies – a science based wiki for documenting all the species of the world

- Wikinews – a collaborative journalism site

- Wikiversity – a free educational resource repository

- Wikidata – a structured data repository used by all Wikimedia projects

- Wikivoyage – a free travel information site

- MediaWiki – the open source wiki software behind all our public websites

(Wikimedia Foundation, 2017)

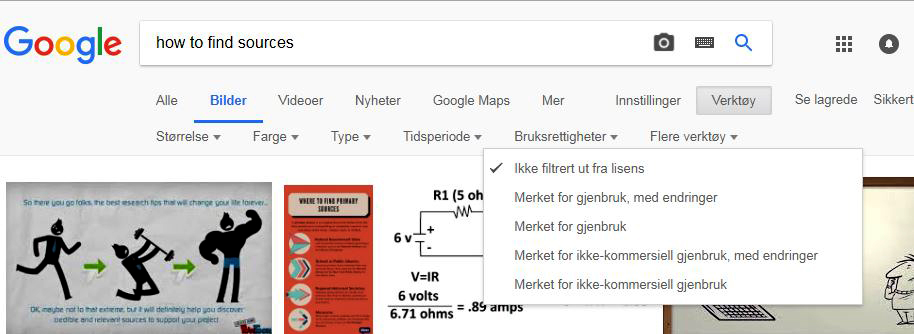

Plagiarism, or the act of passing someone else’s work off as your own, is forbidden by law in most countries. However, it is typically acceptable to use the work of others in your own work as long as you add where you found it and/or who wrote it. You can consider anything * "written" * on the internet available for use as long as you credit the source. How to cite sources will be a topic in chapter 4. When it comes to pictures, most people use the rules specified in Creative Commons to tell us whether it is ok to use their property or not. Read about Creative Commons here.

Look for the CC logo whenever you want to share something, and follow the conditions for sharing that particular type of media. The licencing types can be read on CC's homepage.

When you do a Google search, you can add restriction to define what results will show up. The picture below shows you how.

"It is not what you say, it is the way you say it."

Giving presentations can be intimidating, but they should not be something you fear. Focus on the following points, and you will do just fine!

Plan

Before you do anything else, think about the main topic of what you want your audience to take away from this presentation. Brainstorming is a good place to go from there. Maybe you would want to make a mind map? Check out this page for some help on mapping your mind. Do not be critical at this point; every idea is a good idea when mindmapping.

Structure

Now it is time to plot out the structure of your presentation. Look at your mind map a little more critically now. What do you want to take with you to the next step? Set up your choices as bullet points and move on to the next step.

Write

Often, it is a good idea to write exactly what you want to say and how you want to say it before creating the visual part of your presentation. This will help your presentation to have a good "flow".

Focus

Keep your mind on one of the most important questions: Who will be in the audience? Make sure you use a jargon everyone present can understand.

Rearrange

When you have the full text in front of you, check to see if your points come in a natural sequence. Is something missing? Is something worth throwing away?

Create

Choose what tool you want to use to create your presentation. PowerPoint is familiar and safe, but maybe you would like to try something new? Have a look at one of these lists of presentation tools: CustomShow and Hongkiat.

Minimize

Make sure you keep your presentation simple! The eye is stronger than the ear when it comes to getting to the brain first; if your screen is full of text, most of the audience will not listen to what you have to say before they have finished reading. Have a look at the list of bullet points you made after mindmapping; maybe you can use them on your slides?

Visualise

"A picture is worth a thousand words." A good illustration may be all you need to help you recall all the important details of your presentation.

Introduce

Now it is time to write your introduction. Yes, this late… The reason is that it is only now that you actually know what exactly is in your presentation; which key points were important enough to keep and in what order you will present them.

Prepare

Make sure you know your topic by heart! Your audience expects you to deliver the material with vigour. Ethos, Pathos, and Logos are modes of persuasion used to convince audiences, and you can learn more on this site. Being confident in your material is one of the corner stones of giving a presentation worth remembering; being confident in yourself while presenting your knowledge is another.

Practise

Find someone to practise with, or practise in front of the mirror. You can tape yourself while presenting; that way you can find out if you need to work on your pronunciation, speed, or any other things that could affect the audience's ability to focus on your topic. You can also record yourself talking to check that you speak fluently and without any weird breaks.

Time

While practising, it can be wise to time yourself. You are most likely given a certain amount of minutes to present your material; make sure to keep within that limit. Have a watch nearby while presenting to make sure you follow your schedule.

Venue

If possible, check out the room, seatings, and technology where you are going to give your presentation. Check to see if your computer works with the equipment provided in the room.

Presenting

Think about what you wear and how you present yourself. The first few minutes of a presentation are not the right time to give important information; the audience uses these minutes to make up their mind about you! Remember: be confident. If you have followed the advice above and prepared correctly, you will do very well!

Bibliography

- Chowdhury, F. R. (2015, July 9). Shipping: The role of classification societies. Retrieved from The Financial Express

- Halverson, B. (2010). Retrieved from Lessons Learned in Shipbuilding Inspection

- International Association of Classification Societies. (2015, January). Classifcation societies – what, why and how? Retrieved from International Association of Classification Societies

- Skipsrevyen. (2017, June 1). Retrieved from www.skipsrevyen.no.

- Store norske leksikon. (2015, June 2). https://snl.no. Retrieved August 2017, from Verft, Store norske leksikon.

.