Chapter 1: Maritime English; Why, where, what?

In this chapter you will ….

- get an understanding of the relevance of English requirements according to STCW to all seafarers

- be introduced to the IMO and SMCP

- learn how to build up a sentence and a text

- learn what a topic sentence is

- assess own learning needs.

Maritime English; Why, where, what?

Isn’t English just English? Is there an actual need for a specialized language on board a ship? Well, this might get different answers depending on who you are asking! If you are a person working solely with co-workers from your own nation and culture, you could be close to correct in assuming that the need for a language of its own for seafarers is a bit over the top. Although, mind you, the need for a worldwide language might be necessary, for instance in an emergency trying to get the attention of nearby vessels! On ships with a multicultural crew, the need is more obvious, as also on a ship that is often sailing in foreign waters, dealing with foreign harbours and agents.

Exercise

Fill out and hand-in Mapping of Language Skills.

This is meant to be a tool for both you and your teacher to see how fluent you think you are in English and where you want to be after your classes in Maritime English ☺

Let us have a look at what the world around us has had in mind when it comes to unifying the world of ships, seafarers and ship owners. One of the most world uniting bodies we have is the United Nations (UN). Consisting of almost all the nations in the world, it is fair to say that this is the closest we have to a world democracy. The UN has numerous specialized agencies, and among these we find the one taking care of the shipping industry; The International Maritime Organization (IMO). We are going to have a closer look into IMO later on, but for now we will just point out that the IMO has decided that there is an actual need of a specialized language. This language is called Maritime English and is the subject at hand for you as students for the next two years of education at a Maritime Vocational College in Norway.

Tell a Tale

Inside the IMO, we find the World Maritime University in Malmö, Sweden. Established in 1983, it has already decades of experience in educating youths from around the world. One of the gurus of Maritime English, Associate Professor Clive Cole of the WMU, gives us his thoughts about the need for, and developing of, a global language for seafarers.

Maritime English! Blah! Who needs that?

Aviation English then? Mmm, maybe. Although it’s highly unlikely that passengers would stop and ask themselves whether the plane’s pilot and crew had the skills to communicate effectively in English while coping with the rigours of flying . Of course, it would be totally unacceptable if the crew had only broken English; it being dangerous and most likely illegal.

As it happens, the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), a Specialised Agency of the United Nations just like IMO, has a testing system designed to ensure that pilots are not only technically competent but also in possession of excellent communication skills. If a pilot should fail, then s/he would simply not be allowed to fly! Thank goodness for that!

Actually, the Maritime and Aviation industries are very similar in many ways: they provide transport, they are global, and they require sophisticated equipment and skilled personnel. For all this to work safely and efficiently it is necessary for the Member States to agree on many issues, including that of the crucial aspect of communication. In this respect, while IMO’s “legal framework” is more extensive than that of the aviators since it is a much more complex business, it has yet to adopt global standards for Maritime English competencies.

Interestingly, a word-search in the IMO ‘s legal framework reveals that while Maritime English is mentioned just two times, English is mentioned 878 times! And, if we then add “Effective communication”, 76 times, it is clear that this is a most important aspect.

Why English?

- Wide use – globalisation!

- Language of the maritime industry

- Promoted by IMO – working language; STCW

- Increasingly the language of trade, administration and instruction

- The boss says we must use it!!!

However, language communication is not just an industrial tool but also an emotional and social matter: It strengthens friendship among people speaking different tongues and enjoying diverse cultures.

The Seaborne business includes an enormous variety of occupations and people:

- Personnel training

- Ports/ harbour management

- Administration and finance

- Transport economics & logistics

- Naval aspects

- Design & building of ships

- Maritime law

- Marine insurance

- Seafarers

- Marine environment/ resources management & protection Teachers

- Traders

- Managers

- Administrators

- Lawyers

- Economists

- Ship owners

- Brokers

- Charterers

- Officials

& others…

Seafarers

- We rely on our Seafarers for 90% of our household goods

- BIMCO forecasts a massive deficit of Officers over the next 10 years

- Enhancing global competency on board

- Safer Shipping - The poorer the command of English, the greater the likelihood of fatal accidents

- Having a command of English enhances the quality of life on board – increased social interaction among crew members and decreased sense of isolation

- Short-term

- Required on board (& ashore)

- Necessary for interaction and understanding

- Other immediate goals – professional and social

- Success during training

Longer-term

- Better job/ salary

- Wider network

- Increased mobility

- Global knowledge

- International outlook

WMU Malmö, June 2017 Clive Cole

The International Maritime Organization

The International Maritime Organization (IMO for short) “is the United Nations specialized agency with responsibility for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine pollution by ships.” Quite a large task to manage, but fortunately almost every nation of the world has agreed to work towards a common goal for the shipping industry. The IMO is the tool to reach this goal for safety and security for crews, ships and the environment.

A short presentation of the IMO

“The Organization consists of an Assembly, a Council and five main Committees: the Maritime Safety Committee; the Marine Environment Protection Committee; the Legal Committee; the Technical Cooperation Committee and the Facilitation Committee and a number of Sub-Committees support the work of the main technical committees.” Let us have a look at some of these to see what functions they have.

The Assembly is in practice all Member States of the IMO. You can check which states these are on the IMO website. Here you can also find that some Inter-Governmental and Non-Governmental Organizations can be granted status as observers or consultants to the IMO. The Assembly normally meets every second year, but if one-third of the Members or the Council, give notice to the Secretary-General, they will convene after a notice of sixty days.

In addition to electing the Council, the Assembly also approves IMO’s work programme and is responsible for the financial aspects of the Organization.

The Council consists of 40 member states and is elected for a biennium (two-year term) by the Assembly. The Assembly cannot choose whichever states they prefer. Strict rules regarding this are set in Article 17 of the Convention on the International Maritime Organization, signed in Geneva, 6 March 1948.

The main responsibility for the Council is to follow up on the decisions made by the Assembly. The Council also appoints the Secretary-General, who is approved by the Assembly during its bi-annual session.

The Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) has representatives from all the member states and meets at least once a year. This committee deals with all technical issues such as manning from a safety standpoint, handling of dangerous cargos, marine casualty investigations, ships and port security and so on. We are going to have a closer look at the results of the MSC’s work several times during the two years of study to come.

The Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) also includes all member states and, as its name points out, works to protect the marine environment. The MEPC convenes every nine months. The work of the MEPC will also be addressed later on in your study.

The Secretariat consist of the Secretary-General and a staff of about 300 people from all over the world, situated at the IMO’s headquarters in London. This is the bureaucracy of IMO and where the day-to-day work is carried out.

“The working language is English”

Maritime English (ME) is part of the “family” Language for Special Purpose (LSP). One may think that ME is strictly for the special purpose of technical English, but in fact, it embraces so much more! On board a ship with a multinational crew, one also needs to communicate for social reasons, for everyday matters like food and amenities, and of course, to keep a safe work environment. Ensuring that a message given is received and perceived according to the sender’s intentions is one of the main focuses when those involved speak different first languges. A simple “Yes, Sir!” is not sufficient in all situations, and therefore the IMO requires, under the international convention for Standards of Training, Certification and Watch-keeping for Seafarers, 1978, with amendments (STCW), the ability to use and understand the Standard Marine Communication Phrases (SMCP) for the certification of officers in charge of the navigational watch on board ships of 500 gross tonnage and more.

SMCP

The first official attempt from IMO to create a common working language in the maritime industry can be dated back to 1973 when the Maritime Safety Committee agreed that English should be used for navigational purposes when needed. As a result of this, the Standard Marine Navigational Vocabulary was adopted in 1977. The following years saw a lot of work by the committees, and the Assembly finally adopted the SMCP in 2001.

The main purpose of the standard is to maintain safe sailing at all times. The language of the SMCP is somewhat different from “normal” English. Let us check what is said about this in the official IMO publication:

The SMCP builds on a basic knowledge of the English language. It was drafted intentionally in a simplified version of maritime English in order to reduce grammatical, lexical and idiomatic varieties to a tolerable minimum, using standardized structures for the sake of its function aspects, i.e. reducing misunderstanding in safety-related verbal communications, thereby endeavouring to reflect present Maritime English language usage on board vessels and in ship-to-shore/ship-to-ship communications.

This means, in phrases offered for use in emergency and other situations developing under considerable pressure of time or psychological stress as well as in navigational warnings, a block language is applied which uses sparingly or omits, the function words the, a/an, is/are as done in seafaring practice. Users, however, may be flexible in this respect.

Further communicative features may be summarized as follows:

- avoiding synonyms

- avoiding contracted forms

- providing fully worded answers to "yes/no"-questions and basic alternative answers to sentence questions

- providing one phrase for one event, and

- structuring the corresponding phrases after the principle: identical invariable plus variable.

SMCP covers both internal and external communication. The phrases are mostly in use when it comes to radio communication, but in a stressful situation, it can be a good idea to use the same standards of simplicity in impromptu face-to-face communication on board.

Know the law & Language Learning

Knowledge of the English language also comes in handy while trying to understand the international laws and regulations a seafarer has to take into consideration while performing his duties. For a deck officer, it is important to be able to read and understand a number of these laws, but let us narrow it down to some parts of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) for now. SOLAS sets minimum safety standards for construction, equipment and operation of ships. The very first version of SOLAS was actually made after the sinking of the unsinkable ship Titanic in 1912, setting standards for the amount of lifeboats and other emergency equipment on board.

The convention has been amended many times over the years, and sadly, many of these amendments come as a result of terrible accidents at sea. The version from 1974 is today seen as the main convention, hence you can sometimes see it referred to as SOLAS 1974. The current SOLAS Convention includes Articles setting out general obligations, amendment procedure and so on, followed by an Annex divided into 12 chapters. Open the page about SOLAS on IMO’s webpage to learn more about the different chapters.

Building a sentence

One of the distinctive characteristics in the language of the law is the long sentences. One really has to focus and keep one’s mind clear while reading legal English! The build-up of a sentence is called syntax or sentence structure. All languages have their own syntax, and one of the easiest ways to spot a foreigner is to listen to the order of which the words come in their sentences. That said, the legal language has its own rules, and be it English, Norwegian or any other language, the wordiness, clusters of different parts of speech and amount of foreign word vocabulary and phrases will confuse the reader. You can read more about syntax on http://esl.fis.edu/learners/advice/syntax.htm

In all languages, one hears of different parts of speech, in English there are eight major parts of speech: noun, pronoun, verb, adverb, adjective, conjunction, preposition, and interjection. You can read more about the eight parts of speech on http://partofspeech.org/. Knowing grammar will prove to be helpful while you navigate yourself through legislative legal writing!

Let us have a look at an example from SOLAS, this is parts of the very first sentence:

THE CONTRACTING GOVERNMENTS,

BEING DESIROUS of promoting safety of life at sea by establishing in common agreement

uniform principles and rules directed thereto,

CONSIDERING that this end may best be achieved by the conclusion of a Convention to replace

the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1960, taking account of developments

since that Convention was concluded,

HAVE AGREED as follows:

Had you ever written a sentence like that in one of your papers, your teacher sure would have marked it and asked you to rewrite!

What you need to do is to “uncluster” the sentence, and the easiest way to do so is to first identify the verbs, i.e. what is being done; the action in the sentence. The verb is referred to as the part of the sentence called the verbal.

The verbs in this abstract are: being, promoting, establishing, directed, considering, may be achieved, replace, taking, was concluded, have agreed.

Refresh your knowledge

The next step is to find the subject of the sentence, i.e. who is the doer of the action. Can you find the subject? There is actually only ONE subject for all these verbs, namely the contracting governments.

Now, let us try to list what this subject is supposed to be doing, written in more common English:

Safety of life at sea is important, and it is necessary that all countries agree on some common rules. Since the industry has moved forward, the old agreement from 1960 should be replaced by a new one. The signing countries have agreed as follows:

Academic Writing

The most important thing to keep in mind while writing a text is that it should be comprehensible for your audience! Therefore, asking yourself whom you are addressing should be the first thing you do. Are you writing for fellow crewmembers? For a common newspaper? For a magazine for seafarers? For children? The answer to the question will determine what kind of language you can use. While you are a student in a maritime vocational college, your audience is set by your teacher for each text, and most often, it will be other seafarers, the shipping company, the classification company, or the government. Having this in mind, your technical Maritime English will be understood by the reader. Also, you can expect that your recipient will appreciate the text to be both formal and to-the-point. No room for chitchat and definitely no room for weird abbreviations, SMS language, slang or profanity.

On the word and sentence level, you should note the following:

- Do not use contractions (he will not he’ll, I am not I’m, it is not it’s)

- Be precise! Avoid using words as thing, nice, so (His leg was caught in the thing vs. *His leg was caught in the mooring ropes.)

- Be objective! Limit the use of personal pronouns, use impersonal subjects to state your opinions (It is said that…, it is a common understanding that…). We cleaned the oil spill in the engine room vs The engine crew cleaned the oil spill in the engine room.

- Use words such as apparently, arguably, ideally, strangely, unexpectedly to state your attitude.

- Be genderfluid! By using plural nouns you avoid having to use he or she if you write about someone in general. (Men who want to become captains must be familiar with COLREGS vs Those who want to become captains must be familiar with COLREGS)

- Passive verbs make the text more objective; Tests have been conducted. (the one doing the tests is not mentioned.)

- Verbs such as would, could, may, might can make you seem less of an opinionist. (Norwegian officers have a better education than other nationalities vs Norwegian officers might have a better education than other nationalities)

- Qualifying adverbs (some, several, a minority of, a few, many) can help to avoid making overgeneralisations.

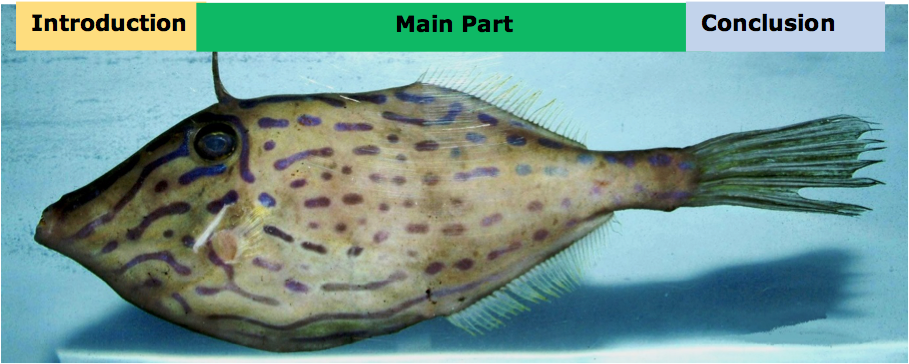

Text structure in a fish!

A formal text should be structured into three main parts, as shown on the picture of the fish. We start at the head with a short introduction, move on to the body, and conclude at the tail of the fish. As you can see, the introduction and the conclusion are smaller parts of the text. The content is taking up more space and requires the body of the fish/text to have enough room to be debated, explained, and/or presented sufficiently.

Credit: NOAA/NMFS/SEFSC Pascagoula Laboratory; Collection of Brandi Noble, NOAA/NMFS/SEFSC. (Adapted)

In short

In short, one can summarize a text like this:

- Introduction: Tell me what you are going to tell me.

- Main part: Tell me!

- Conclusion: Tell me what you have told me.

State your opinion

All good texts have a thesis statement, a topic sentence, in the introduction. This is what will make your readers decide whether they will continue reading or not. A thesis statement shall provide the reader both the what and the why of your text. It might seem weird to give the answer first and then continue the text with the arguments that lead to the answer, but this is how it is done.

A thesis statement might change in the course of writing! You might change your mind while diving into the material at hand. No worries; just change the thesis statement. Some even say that they write the main part of the text first, then continuing to the conclusion before summarizing the whole thing and calling it an introduction.

More

Have a look at this video to learn more about thesis statements.

In this chapter you have learnt...

- that IMO has decided that there is an actual need of a specialized language; this language is called Maritime English.

- that the IMO is a body within the UN-system and consists of an Assembly, a Council and five main Committees and a number of Sub-Committees.

- what STCW and SMCP is.

- that SOLAS sets minimum safety standards for construction, equipment and operation of ships.

- that legal language needs special attention.

- parts of speech in English.

- that academic writing has some rules you need to remember.

Bibliography

IMO. (2002). IMO SMCP. London: International Maritime Organization.

IMO. (n.d.). About IMO. Retrieved 2017, from imo.org:

[http://www.imo.org/en/About/Pages/Default.aspx]

(http://www.imo.org/en/About/Pages/Default.aspx)

IMO. (n.d.). Structure of IMO. Retrieved 2017, from http://www.imo.org/en/About/Pages/Structure.aspx