Chapter 2: The Seafarer’s Playground

In this chapter you will ….

- find a quick look at parts of the maritime history

- learn about continents, regions, and countries

- learn something about how the shipping industry looks today

- learn the names of different types of ships

- find out what modal verbs, prefixes, and suffixes are and how to use them

- learn more about paragraphs and topic sentences

- learn about signalling words

Historical view

Maritime history did not start with oil tankers, nor with sailboats; even the Neanderthals hunted marine mammals! With only canoes, their range was limited, but change was soon to come. The science of navigation, in use already 5000 years ago on the Indus River, combined with the construction of ships with sails, marks the start of trade routes. Since then, the routes have expanded, and today the seafarer’s playground has no limitations.

Vikings

Historically, we know that the Vikings expanded their horizon by sea both to the East to Miklagard (today’s Istanbul) as early as 839, and to the west to Vinland (today’s America) in 1002. The Viking ships were built for either war, trade, or transport; each purpose demanding its own kind of ship. Vikings used the Knarr for voyages in the open sea while graceful longships were mostly used for transporting their troops during invasions and raids.

The Scandinavian countries still have a place amongst the top seafaring nations today, with Norway as the greatest. When the IMO Assembly elects members for the Council, Norway is often chosen in the category of states with the largest interest in providing international shipping services.

“Rule, Britannia!, Britannia rule the waves”

If you have ever watched the Last Night of the Proms, aired from the Royal Albert Hall once a year, you are bound to remember the audience singing “Rule Britannia”! If you haven’t, look it up on YouTube to get the gist.

“The first public performance of ‘Rule, Britannia!’ was in London in 1745, and it instantly became very popular for a nation trying to expand and ‘rule the waves’. Indeed, from as early as the 15th and 16th centuries, other countries’ dominant exploratory advances encouraged Britain to follow. This was the Age of Discovery, in which Spain and Portugal were the European pioneers, beginning to establish empires. This spurred England, France and the Netherlands to do the same. They colonised and set up trade routes in the Americas and Asia.”

Colonisation - The British Empire

As you can see from the map, the Britons extended far beneath the borders of Jolly Old England! The saying “The empire on which the sun never sets” was definitely true when the British Empire was at its largest. “By 1913, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, 23% of the world population at the time, and by 1920, it covered 35,500,000 km2 (13,700,000 sq mi), 24% of the Earth's total land area. As a result, its political, legal, linguistic and cultural legacy is widespread.”

After seeing the widespread area in which English was the language of the rulers and lawmakers, one can surely understand how English became the lingua franca. According to Cambridge dictionary, lingua franca means “a language used for communication between groups of people who speak different languages”. The term originates from the period when the Mediterranean countries were the ones ruling the waves and the world.

Learn more about Maritime history on Wikipedia

“He’s got the whole world in his hands”

As you most likely know, this song is not really about a seafarer, but it could be! With an engine officer’s certificate, you are free to roam the seven seas; the whole world lies before you. With the world as your office, you are responsible for learning more beyond the haven where you have spent most of your life.

“The Seven Seas”

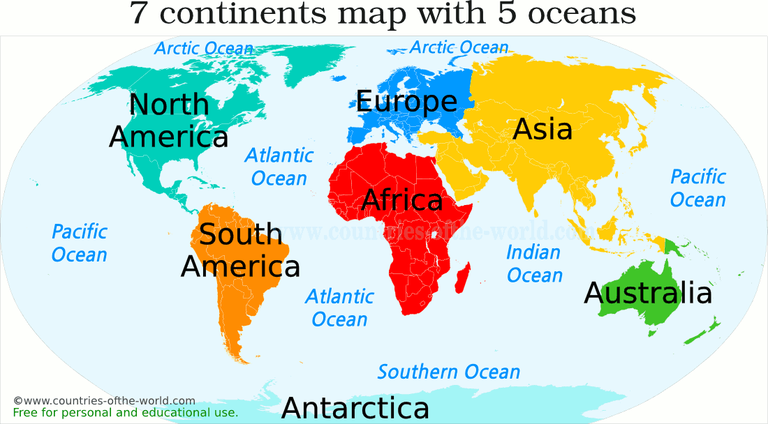

We have all heard stories of sailors “sailing the Seven Seas”, but where and what are these seas? In modern times, we list the following oceanic bodies of water to be the infamous Seven Seas: the Arctic Ocean, the North Atlantic Ocean, the South Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the North Pacific Ocean, the South Pacific Ocean and the Antarctic (Southern) Ocean. As you can see from the map, there are actually only five oceans; the old way of naming the oceans split the Atlantic and the Pacific into North and South, thus making it to a total count of seven.

Continents, regions, and countries

Today, close to 200 countries are acknowledged by international experts and authorities. It is widely accepted to divide the world into seven regions, commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in size to smallest, they are: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia. The U.N. Statistics Division groups countries into regions and sub-regions rather than into continents. Visit http://unstats.un.org to learn more!

The word continent originates from the Latin terra continens which can be translated into “connected land”. Originally, the term was used for areas of land not separated by water. Today, we think of continents as large areas of land, not necessarily separated by wide areas of water. If that was the case, Europe and Asia would be regarded as one continent.

In terms of area, the biggest country of the world is Russia, with almost twice the area of number two, Canada. The smallest is the Vatican State with its 0.44 square kilometres and Monaco, 1.9 square km. The most populated countries are China, India and the U.S. You can check a number of interesting facts about all the world’s nations on the World Factbook, a site from the US Central Intelligence Agency.

“When in Rome, do as the Romans”

What will you need to know when you visit foreign ports? Seafarers encounter people from all over the world, such as fellow crewmembers, stevedores, pilots, ships chandlers, and many more. Being part of a multinational crew, with all its positive, and possibly negative, aspects, is the topic of a later chapter.

Tell a Tale

Read what a captain who has lived many years in Singapore, Captain Oddbjørn M. Bugge, has to say about his experience as a Norwegian seafarer working in both the shipping and offshore industries worldwide:

For me, as for many others at the time, my seafaring career started early. I left home at the tender age of 15 to join the square rigger “Sørlandet” for pre-sea training in February, 1959, with a firm aim to be a Captain by the time I reached 30 years of age.

My education was 7 years of “Folkeskole” (Primary School), with a rudimentary command of English and a limited understanding of the world I was about to join. My world view was coloured of the general view at the time, that Norwegians were “the best seafarers in the world” and Europeans somehow superior to other races. (This was at the end of the Colonial era after all).

At first, I followed a fairly normal path, going the grades on Norwegian ships in worldwide trade and taking maritime education as a deck officer, up to Navigator I and eventually to Master Mariner.

This changed somewhat in 1967, when I found myself working in S.E. Asia. I sailed on a variety of ships, still under Norwegian flag but now with only a few Norwegian officers and a mixed crew of Singapore Chinese, Malay and Indonesian origin. I also starter to regard Singapore as “home”, as that was my regular port of call and became my base from then on.

In 1968-70, I was Chief Officer on ships trading between Australia and the South Pacific Island, with Kanaka crew from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, who were largely illiterate, but never complained about anything. To deal with them I had to learn to use their language, “Tok Pisin”

Because I had a full red beard at the time, my name in Tok Pisin was “Masta Grass”.

I left the last of those ships in August 1970, which was also to be my last ship under Norwegian flag.

After a few weeks of holiday in Singapore, now with a newly minted Master Foreign Going License, I got a job as Navigator for a big American Offshore Marine company with five boats working in S.E. Asia at the time. All were typical Gulf of Mexico type boats and flying the American flag.

This was my first introduction to the Offshore Industry. My job was to go on board any of the boats when they were going to/from working areas in Malaysia, Indonesia or Thailand to guide them safely to their destination since the American Skippers were mostly Cajuns from the bayous of Louisiana, who could not navigate when operating out of sight of land or platform. Some could not even read or write and their spoken English was difficult to understand for anybody, not least for a “foreigner” like me.

After 2 two and a half months, I was called up to Marine Department in Singapore to explain how I could be Master on five boats simultaneously. It appeared that a photo copy of my license had been used to clear out all the boats belonging to this company. Needless to say, I quit on the spot.

After 2 two and a half months, I was called up to Marine Department in Singapore to explain how I could be Master on five boats simultaneously. It appeared that a photo copy of my license had been used to clear out all the boats belonging to this company. Needless to say, I quit on the spot.

Hopefully these kind of things couldn’t happen today, anywhere in the world.

After some years back in the shipping industry and getting my first command at age 27, I had a kind of midlife crisis at 30. I had reached my goal of being Captain at 30 and could now look forward to 30 more years of sailing old rust buckets around the world. I decided it was time for a change and started my own company in Singapore with a view to becoming a Ship owner one day.

Unfortunately the shipping crisis caused by the first oil price shock put a stop to those plans, and I ended up back in the Offshore Industry instead.

A friend of mine introduced me to a newly establish British Marine Warranty Survey company that had set an office in Singapore. I had never even heard of anything called Marine Warranty Survey, but was accepted as a Freelance Surveyor and given a quick introduction into the business, whereby I became an “instant expert” in the art of Marine Operations and Rig Moving.

I had an introductory visit with another Surveyor, on loan from the London office, to a drilling rig being in Singapore for repairs. A few days later, I was back on board the same rig as Warranty Surveyor for a tow to the Java Sea. This was in the “cowboy days” in the offshore industry, with mainly Americans in charge, both on the rigs and ashore, as they were in the oil companies the rigs were working for. The standard of living quarters and working conditions were also American standard. A kind of a cultural shock for someone who, on my last ship had a three room flat and a deck to myself, not to mention a Captain’s Boy to look after my smallest needs. But, if you are willing to adapt you can get used to most things, especially the last.

After nearly four years as Freelance Surveyor, working all over S.E. Asia, China, Japan and the Indian sub-continent, I needed a change. I got a job as Captain on an American owned and operated, but Panama flagged, Drillship working in S.E. Asia. The permanent crew on my shift consisted of about 40 persons of 19 different nationalities. Local crews were engaged in the country we operated in at various times. In addition, there would be service personnel of various nationalities, for a total of 110 persons. I was the only Norwegian working for that company at the time.

This worked very well, since nationality was not an issue and everybody got judged based on their merits and personality, not nationality or race. When we at one time got too many of one nationality and they started to form a separate group in the mess hall and recreation room, we requested a transfer of some to restore balance – a good and happy ship.

Over the years that followed, I worked in various positions in the Offshore Oil & Gas industry, mostly involved with Marine Operations, but also in Management and as Marine Consultant for Oil Companies, Drilling Contractors and Offshore Construction Companies. The last few years I have been back to be Freelance Marine Consultant and Surveyor, based in Singapore. Now I am retired in Norway.

To conclude: For nearly 60 years I have worked worldwide with people of all races, religions and nationalities. Some have been of the highest calibre and level of skills and education, others with only the most basic of knowledge and understanding of the tasks at hand. Many with only rudimentary education, if any, as I had when I started out.

What have I learnt from all those years?

- Forget the prejudices you were taught about the superiority of your country of origin.

- NEVER allow yourself to feel inferior to anybody, no matter what background.

- You cannot be discriminated against, unless you feel inferior.

- NEVER judge a person by the colour of the skin, their race, religion or nationality.

- Learn the basics of the culture of the country and region you are living and working in.

- Learn at least some of the language of the people in the country you are living, especially if their English is weak. This is important on a social level, as well as for cultural understanding.

Some good advice for those who are looking at an international career:

- Fluency in English is important, no matter where in the world you work.

- Most global companies use English as their working language, especially in a multi-cultural setting. Even if you are the only non-native speaker in a meeting, unless you are fluent in the local lingo, insist on the meeting being conducted in English.

I have seen meetings breaking down into a “babel” of languages, only for those who are good at manipulating such situations, to let the minutes of meeting reflect their agenda.

The shipping industry today

In the section about shipping from a historical point of view, you read about how ships have been essential for trade and exploration for quite some time. Let us have a look at some numbers concerning shipping to see what you are really getting into by becoming a sailor.

The World Fleet

The following is from https://www.statista.com/:

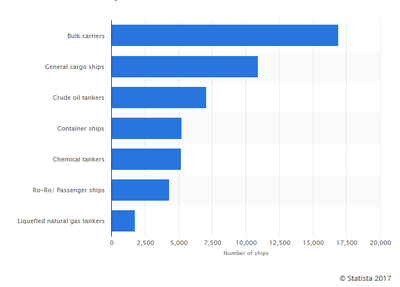

How many ships are there in the world? The number of ships in the world exceeds 50,000: as of January 2016, there were 51,405 ships in the world's merchant fleets. Bulk carriers – ships designed to carry solid bulks such as coal and grains – are ranked as the most common type of ship in the global merchant fleet, accounting for about a third of the fleet: There were almost 17,000 such ships in the merchant fleet as of the beginning of 2016. The willingness to embrace larger ships with increasing capacities remains high in the industry. Bulk carriers had a combined capacity of around 112 million tons deadweight in 2016, about half the volume of container ships’ combined capacity, which came to around 244 million tons deadweight.

Overview of Number of ships in the world merchant fleet as of January 1, 2016, by type.

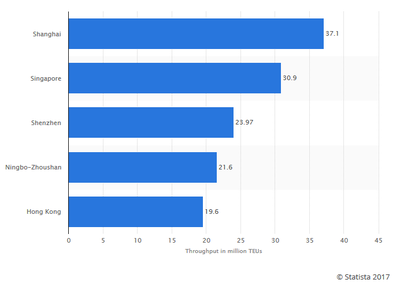

Statista also has statistics on the world's largest container ports:

Ports are hubs that welcome marine vessels so they can dispatch or discharge cargo. In terms of value, seaborne trade carried by container ships is the most important category of waterborne freight, and container handling is one of the key sources of revenue produced by the operation and management of a port. Intermodal containers usually have a capacity of one or two twenty-foot equivalent units, a standard unit of measure which is often being abbreviated to TEU. On a global scale, the busiest ports are located in Asia, the largest ones being Shanghai, Singapore and Hong Kong. The Port of Los Angeles and the adjoining Port of Long Beach together form the largest port in the United States. The cities of Rotterdam, Hamburg and Antwerp are home to the largest ports in Europe.

With a global market share of 8.2 percent in 2013, Singapore’s PSA International is the world’s leading marine terminal operator, followed by Hutchison Port Holdings, which is headquartered in the British Virgin Islands. PSA International operates several ports around the world, generating about 2.6 billion U.S. dollars (or around 3.57 billion Singapore dollars) in revenue in 2015. The Port of Los Angeles is operated and managed by the City of Los Angeles.

Exercise:

Search the internet to find the

- Busiest cruise port

- Largest fishing port

- Biggest oil port

Basic Ship Knowledge

To know the proper maritime terms for the different parts of the ship is expected knowledge for a seafarer. When we hear landlubbers saying "hard left" we tend to smile. However, even though the terms are well known in Norwegian, we might need to spend some time learning them by heart in English as well. In addition, we also need to have a vocabulary for the different movements the ship experience, as well as positions in relation to the vessel.

The video under gives you the most necessary vocabulary in question

Different types of ships

As you well know, there is a myriad of ships sailing the seven seas and each one has a purpose. The table below categorises ships’ types.

| Dry Cargo – Unit cargo | Dry Cargo – Bulk cargo | Liquid Cargo | Passenger ships |

|---|---|---|---|

| Container vessel | Bulk carrier | Crude carrier | Passenger ship |

| Roll-on/Roll-off | Ore carrier | Product tanker | Car and passenger ferries |

| Heavy-cargo vessel | Chemical tanker | Cruise ship | |

| Refrigerated ships | LPG/LNG carriers | ||

| Cattle ship |

Multi-purpose ship

| Navy vessels | Fishing | Dredgers etc | Work ships |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aircraft carriers | Trawlers | Trailing hopper suction dredger | Crane vessels |

| Cruisers | Other types of fishing vessels | Cutter suction dredger | Buoy-layers |

| Destroyers | Rock-dumper | Cable-layers | |

| Frigates | Oil-recovery vessels | ||

| Submarines | Shear leg cranes | ||

| Mine sweepers |

| Auxiliary vessels | Yachts | Various | Offshore material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seagoing tugs | Motor yachts | Hydrofoils | Drilling rigs/Jack-up |

| Harbour tugs | Sailing yachts | Floating dock | Drill-ships |

| Icebreakers | Submersible platform | Pipe layers | |

| Pilot vessels | Pontoons, barges | Floating (Production) | |

| Coast guard vessels | Storage and Offloading vessel F(P)SO | ||

| Research vessels |

In a later chapter, we will have a closer look at the process of building a ship.

Exercise:

- Make a presentation about a ship.

- Feel free to choose one where you have worked.

- Place it in one of the categories above and describe why it fits into this category.

- Present the ship for your classmates and teacher, either in groups or in front of the entire class.

Task

The following text is from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)’s Review of Maritime Transport 2016. The complete review can be found here.

Answer the following questions, using your own words:

- According to the text, what can influence shipping in the future?

- Is CO2 emissions from shipping expected to rise or fall in the future?

- Use the Internet to find out what the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is. Write 250-300 words to summarize what you found. Remember to cite your sources!

Although many signals are negative, seaborne trade continues to grow, with volumes exceeding an estimated 10 billion tons in 2015. While a slowdown in China is bad news for shipping, developing countries other than China are increasingly entering the shipping scene and have the potential to drive further growth. The lifting of some sanctions on the Islamic Republic of Iran is expected to stimulate crude oil trade, as well as non-oil sectors.

(…)

Technology, innovation, the data revolution and e-commerce can significantly transform and disrupt the shipping industry, generating both challenges and opportunities, including with regard to efficiency gains, new business models, use of the Internet, digitization, efficient logistics, effective asset management and the greater integration of small and medium-sized enterprises. Developing countries may leverage related trends to cut costs, raise productivity, develop capacity – including skills and knowledge – and enable access to new businesses opportunities.

How these trends will materialize on a broader scale remains unknown, yet it is nevertheless important for all countries – in particular in developing regions – and their transport industries to keep these developments in mind, monitor their evolution and assess their particular implications for their transport and logistics sectors and, more broadly, for their economies, societies and environments. An improved understanding of the trends and their implications may help countries ensure that these are effectively integrated into relevant planning and investment-related decision processes, and aligned with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Finally, the international climate agenda can be expected to further shape the maritime transport operating landscape, as the sector faces the dual challenge of climate change mitigation and adaptation (for a more detailed discussion of the climate change–maritime transport nexus, see the Review of Maritime Transport, 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015). Future trends in emissions from international shipping remain uncertain and subject to international efforts and commitments to curb greenhouse gas emissions including the efforts under the frameworks of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Curbing greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping is an imperative, as freight transport, including maritime transport, grows in tandem with the global population, consumption needs, industrial activity, urbanization, trade and economy. Despite the current slowdown in the growth of world seaborne trade, maritime freight volumes and demand for maritime transport services are expanding. At the same time, shipping’s heavy reliance on oil for propulsion translates into significant emissions of airborne pollutants and greenhouse gases. According to IMO data, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from international shipping were estimated at 2.2 per cent of total emissions in 2012 and are projected to increase by 50–250 per cent by 2050, depending on economic growth and the global energy demand. As the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change does not refer to emissions from international shipping, continued work under the frameworks of IMO and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is of critical importance.

Know the Law & Language Learning

Shall, must, will, can… Modal verbs in legal language

Both English and Norwegian use modal verbs to express possibility, prediction, necessity etc. Modal verbs are part of the group we call auxiliary verbs. Auxiliary verbs are often called helping verbs; have, be, will, and do are all used to help forming questions, to write a negative sentence, a compound tense, or a passive verb structure. Read more about modal verbs on the British Council site before you move on to the next paragraph, where we will have a look at modal verbs in laws and regulations.

As you learned in chapter 1, the language of the law can be both wordy and difficult to grasp as a layperson. It is also a known fact that this is quite a conservative language; it does not change overnight, and in some areas, not even over decades! The legal language, the one used to talk about the laws, can be a bit more modern, but still hard to get your head around if you do not use it frequently. A law takes into consideration all possible outcomes of a situation, and can be either regulative or constitutive. A constitutive law defines an action or praxis, whereas a regulatory law tells us how an action is performed well.

Short description of the modals:

- Must: compulsory, important, necessity

- Shall: obligation, order

- Will: obligation, prediction

- May/can: permission, possibility

- Should: recommendation, advice

- Would: request, permission

- Could: possibility, request

- Might: probability, suggestion

Exercise:

-

Find the modal verbs in this abstract from SOLAS:

Regulation 13

Issue of certificate by another Government

A Contracting Government may, at the request of the Administration, cause a ship to be surveyed and, if satisfied that the requirements of the present Regulations are complied with, shall issue certificates to the ship in accordance with the present Regulations. Any certificate so issued must contain a statement to the effect that it has been issued at the request of the Government of the State whose flag the ship is or will be entitled to fly, and it shall have the same force and receive the same recognition as a certificate issued under Regulation 12 of this Chapter.

-

Try to rewrite the sentences into “normal English” sentences. You might find some help in Language learning in Chapter 1.

Prefix

Prefix

A prefix is a letter or set of letters added to the beginning of a word.

Examples of prefixes: un-, multi-, cyber-, a/an-, counter-, dys-, bi-, mal-, im-. *

Adding a prefix changes the meaning of the word: natural – unnatural, cultural – multicultural, space – cyberspace, symmetric – asymmetric, circulation – counter circulation, functional – dysfunctional, annual – biannual, practice – malpractice, perfect – imperfect. As you can see, some of the new words are written in two words. This is an area where Norwegians tend to make mistakes; either in Norwegian or in English, or maybe even in both languages. In Norwegian, we most often write these in one word, while English uses more hyphenations or splits it into two words. Also note that the rule from article – noun applies while using a/an as a prefix: use a before a consonant sound and an* in front of a vowel sound.

Another pitfall may be the usage of the prefixes ig-, il-, im-, and in-. There is a rule you can try to learn: ig- (before gn- or n-), il- (before l-), im- (before b-, m-, or p-), in- (before most letters), or ir- (before r-)

Exercise:

Try to make new words by adding a prefix to the following:

Understand – Activate – Balance – Legal – Regular – Alphabetic – Adequate – Function – Inflammatory – Littoral – Stop – Normal – Meter – Possible – Chromatic – Force – Replaceable

Suffix

Suffix

A suffix is a letter or set of letters added to the end of a word.

Examples of suffixes: -ful, -ment, -s, -age, -hood, -ist, -ism, -ance/-ence, -ity/-ty, -able.

Adding a suffix often changes the word class: govern (verb) – government (noun), respect (verb) – respectful (adjective), day (noun) – daily (adjective), weak (adjective) – weaken (verb). You will also see that many words change spelling while adding a suffix: Britain – British, fame – famous, economy – economise

Exercise:

Try to make new words by adding a suffix to the following:

State – Ready – Forget – Permit – Bag – Arrive – Brutal – Enter – Flex – Gold – Beauty – China – Poet

Academic Writing

While writing, and speaking, it is important that the information you give flows easily from sentence to sentence, as well as from one paragraph to the next. In this chapter, we will look into paragraphs, topic sentences and signalling words.

Paragraphs

Each paragraph should focus on one topic or idea. The topic of this paragraph is to describe what a paragraph is. The length of a paragraph is determined by how complex your topic is, but as a rule, a paragraph should be at least three sentences long. If shorter, check to see if these sentences might just as well be part of the paragraph before or after. On the other hand, it should not be too long, either! If you find yourself writing half a page in one paragraph, it might be wise to see if you can split it into two or three parts. As a rule of thumb, one can say that an A4 page should include at least two to three paragraphs, depending on the topic, of course!

A new paragraph is shown by a line break. In a text editor such as Word, the default setting is to hit the Enter-key on the keyboard to make a line break. Read more about the technical part of making paragraphs on this site. Remember that each paragraph should start with an introduction to the paragraph’s main focus or idea. From the first chapter, you may remember that a text can be structured like a fish. The same goes for paragraphs; after the introductory sentence, you move on to discuss or describe your topic in the main part, before concluding with a sentence or two at the end of the paragraph.

- Use the first sentence to state what you want to talk about, and use signalling words (see below) to show the place of this particular paragraph in the text as a whole.

- Use the middle part to give examples, show consequences, and examine opposing ideas.

- Use the last part to conclude on the middle part, and while making a natural “flow” over to the next paragraph.

Topic sentences

In English, more often than in Norwegian, it is common to start each paragraph with a topic sentence. We have already talked a little bit about how to start a paragraph, but let us have a closer look. A topic sentence should state what you are going to talk about, but also capture your reader’s attention to make them want to read more. It should also be cohesive; binding the paragraph together with the rest of your text. Writing a good topic sentence might take some practise; it can be hard to put down in just one sentence what you want to express within a full paragraph. A topic sentence should state an opinion, but at the same time be formal. Signalling words may be a good place to start looking for what to put in the beginning of a topic sentence.

Signalling words

Signalling words, or transmission words, will help you connect the ideas you present, show that your text has coherence, and guide your readers to agree with you at the end of your text. We can use signal words to show cause and effect: When/because/since, As a result of / because of. Some of the more common signalling words are however, thus, for example, finally, on the other hand, nevertheless, furthermore, in particular, in fact, also, in addition, therefore, then, for instance, moreover, but, yet, and first, second, etc. You can read more about signalling words on this site.

Exercise:

- Use the internet to find more signalling words. Write sentences using at least five of the new signalling words you have just found.

- Try to make a topic sentence on each of these subjects:

a) The future of shipping.

b) It is safer to work in fishery than in the offshore industry.

c) Getting your education at a vocational college.

In this chapter you have learnt…

- a little bit about maritime history.

- about oceanic bodies of water .

- the difference between continents, regions, and countries.

- numbers about today's shipping industry.

- names for different types of ships.

- what modal verbs are and how they are used in legal language.

- about prefixes and suffixes.

- about paragraphs, topic sentences, and signalling words.

Bibliography

- Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Cambridge Dictionary - Lingua franca. Retrieved from Cambridge Dictionary: http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/lingua-franca

- Johnson, B. (n.d.). Rule Britannia. Retrieved 2017, from Historic UK: http://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Rule-Britannia/

- Statista. (2017). statista.com. Retrieved from Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264171/turnover-volume-of-the-largest-container-ports-worldwide/

- Store norske leksikon. (n.d.). Vikingskip. Retrieved 2017, from - Norges historie: https://snl.no/vikingskip

- Stringer et al. (2008, September 22). Neanderthal exploitation of marine mammals in Gibraltar. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805474105

- UNCTAD. (2016). Review of Maritime Transport 2016. Geneva: UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION. Retrieved 2017, from http://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=1650

- van Dokkum, K. (2007). Ship Knowledge (4. ed.). Enkhuizen: DOKMAR.

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). British Empire. Retrieved 2017, from Wikipedia - The Free Encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire